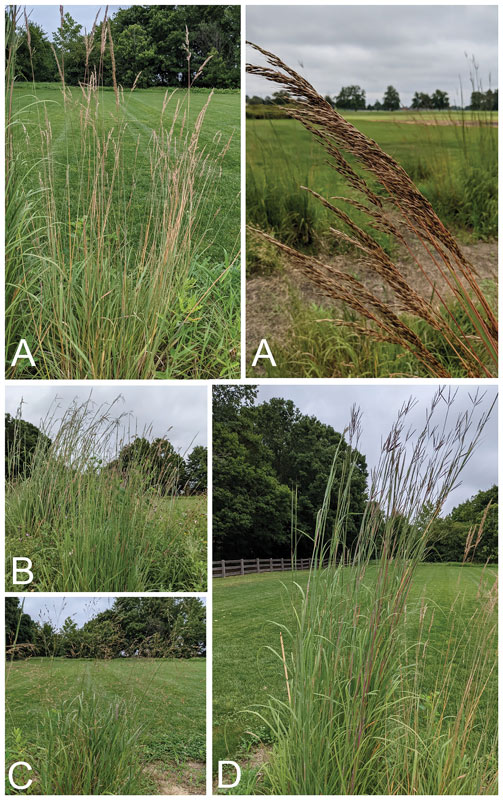

Figure 1. Little bluestem, tall fescue and fine fescue in a minimal-mow natural golf course area at The Pfau Course at Indiana University in Bloomington, Ind. Photo by Aaron Patton

Golf courses typically have two different rough areas: a primary rough, which is mowed between 1.5 and 4.0 inches (3.8 and 10.16 centimeters) and causes moderate difficulty in golfer strokes; and a secondary rough, which is more often located in out-of-play areas and consists of grasslands or other natural areas (Figure 1, above).

A GCSAA survey estimated there were 2,301,808 acres of golf facility land in the United States in 2015, of which 26% was composed of natural areas (5). Furthermore, 21% of the total natural acreage consisted of native grasslands of these natural/native/non-mowed areas. These secondary golf course rough areas that contain grasses, forbs and wildflowers are colloquially referred to by a variety of names by golf course superintendents, including “native areas,” “native rough,” “naturalized areas,” “natural rough,” “naturalized rough,” “minimal-mow areas” or “no-mow areas.” Here, we will refer to these areas as “minimal- to no-mow areas.”

Minimal- to no-mow areas on the golf course are maintained with minimal inputs (e.g., pesticides, fertilizer, irrigation, mowing), and efforts to increase the acreage of these areas on golf courses continue to be promoted as an approach to not only reduce overall inputs and maintenance costs (5), but also to support plant biodiversity, wildlife, pollinators and other beneficial insects (3, 4). However, some inputs are occasionally still required in these areas to maintain aesthetics and playability. Most often, these inputs may include mowing one to two times per year or weed control with herbicides to eradicate unwanted, encroaching vegetation and promote desired plant species.

Weed control can be challenging in these minimal- to no-mow areas because there is often a large biodiversity of perennial species, both warm-season (C4) and cool-season (C3) grasses, planted within sites (8, 9, 10). Open field burning may be one effective solution for weed control. However, some regions have restrictions because of concerns over air pollution and public safety issues (8). Depending on site and environmental conditions, some minimal- to no-mow areas may become infested over time with invasive weeds, especially grassy weeds, which will decrease aesthetics and the functional properties of these areas.

Only a few studies have investigated the safety of over-the-top applications of postemergence herbicides for selective grass control on multiple grass species (6, 7). Our objective was to evaluate the tolerance of 11 grass species used in minimal- to no-mow turf areas to three postemergence herbicides applied at use label and two-fold recommended label rates. Our assessment of postemergence herbicides for selective grass control for minimal- to no-mow areas should help equip golf course superintendents to control weeds and promote the potential for greater biodiversity of grass species in minimal- to no-mow areas.

Methods

Field studies were conducted in 2018 and 2019 at the W.H. Daniel Turfgrass Research and Diagnostic Center at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Ind., to investigate the effect of herbicide treatments on 11 grass species maintained in a minimal- to no-mow secondary rough area (Table 1 and Figure 2, below). Prior to the experiment, all plants were grown in a greenhouse and then transplanted into field plots on June 15, 2018. Any plants that had unacceptable quality after 2018 were transplanted into plots from an adjacent field nursery on May 20, 2019, for Year Two of the experiment. Plots were mowed only once in the spring at 4 inches prior to 100% spring green-up.

Figure 2. A few of the grass species included in the experiment: (A) indiangrass, (B) little bluestem, (C) switchgrass and (D) big bluestem. Photos by Ross Braun

Seven herbicide treatments, including a non-treated check and two rates of quinclorac, sethoxydim and topramezone, were applied with a CO2-pressurized boom sprayer equipped with XR TeeJet 8003VS nozzles calibrated to deliver 87 gallons/acre (813.8 liters/hectare) at 30 pounds per square inch on Aug. 23, 2018, and June 11, 2019 (Tables 2 and 3). The low and high herbicide rates were based on the label-recommended and twice the label-recommended rates.

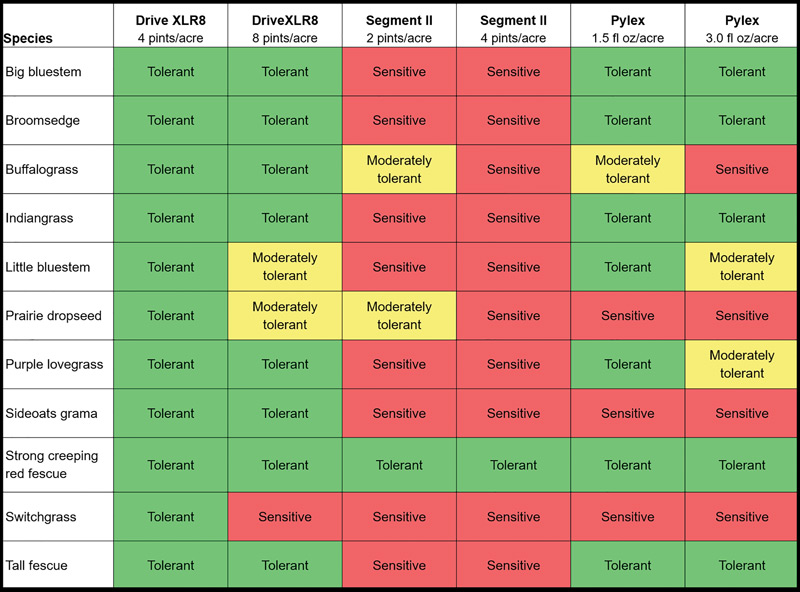

Plant injury (0 to 100%) and plant quality (1 to 9 scale, where 9 = highest quality/health) were visually estimated for each species when treatments were initiated and every 14 days after application. A separate analysis for each grass species was conducted for each year to limit confounding effects from plant maturity differences between years. After analysis, overall categorical ratings of “tolerant” (i.e., acceptable plant injury of <20%), “moderately tolerant” (21% to 35% plant injury) and “sensitive” (>35% plant injury) were developed based on plant injury and quality ratings across both experiment years (Figure 3, below).

Figure 3. Overall categorical ratings, based on plant injury and plant quality data, for one application of herbicide treatments tested on various grasses in 2018 and 2019. Generally, ratings of “tolerant,” “moderately tolerant” and “sensitive” correspond to observed responses of <20%, 21% to 35%, and >35% plant injury, respectively, across both experiment years. Golf course superintendents should be cautious conducting sequential applications during the same growing season, as this could exacerbate injury on the desirable grasses.

Herbicide tolerance

Drive XLR8

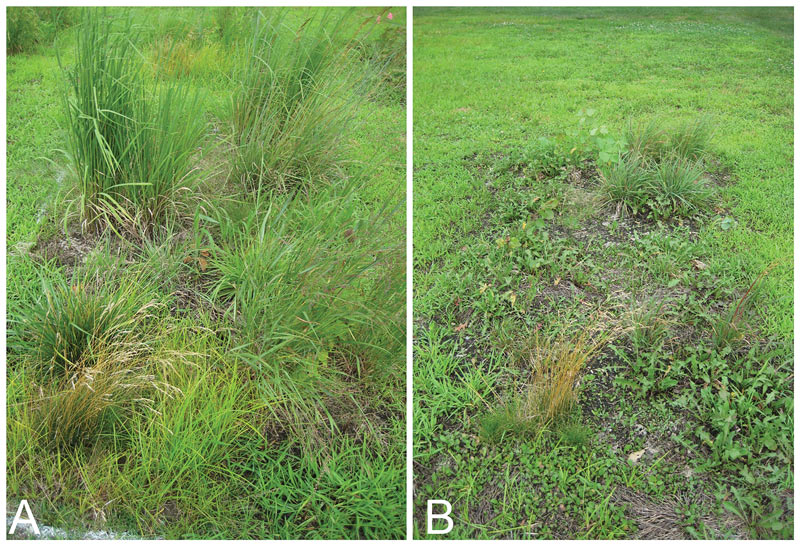

Little to no plant injury occurred across the 11 grass species when Drive XLR8 (quinclorac, BASF) was applied in a broadcast application at label-recommended and twice the label-recommended rates in both years, with a few exceptions (Tables 2 and 3; Figure 4). The exceptions were little bluestem, prairie dropseed and switchgrass, which were only moderately tolerant (21% to 35% plant injury) or sensitive (>35% plant injury) to Drive XLR8 applied at twice the label-recommended rate (Figure 3). Overall, Drive XLR8 applied at the label-recommended rate can be an effective option for grassy weed control in minimal- to no-mow rough areas containing any of these 11 grasses (Figure 3).

Figure 4. Influence on plant injury of 11 grass species in 2019 at 28 days after a single application of either (A) Drive XLR8 applied at a rate of 4 pints/acre, or (B) Segment II applied at a rate of 2 pints/acre. Photos by Ross Braun

Segment II

With the exception of strong creeping red fescue (data not shown), Segment II (sethoxydim, BASF) at both herbicide rates significantly injured all grass species (Tables 2 and 3; Figures 3 and 4). Multiple subspecies of the Festuca rubra complex, including strong creeping red fescue, have been reported to be tolerant to sethoxydim at multiple application rates similar to those in this experiment (2). Further, strong creeping red fescue included in this experiment is one of five commonly used fine fescue taxa in turfgrass systems that are often used together in mixtures (1). Therefore, we need further research to investigate herbicide tolerance differences among the five fine fescue taxa to differentiate and reduce the likelihood of making potentially inaccurate claims for the herbicide safety of the entire fine fescue grouping (1). Our results demonstrate sethoxydim can be safely applied in minimal- to no-mow areas that contain mainly strong creeping red fescue.

Pylex

Injury from Pylex (topramezone, BASF) exhibited the most variation among grass species, herbicide rate and years (Tables 2 and 3; Figure 3). Grasses tolerant (<20% injury) to Pylex at both rates were big bluestem, broomsedge bluestem, indiangrass, strong creeping red fescue and tall fescue (Tables 2 and 3; data not shown for strong creeping red fescue). Little bluestem and purple lovegrass were tolerant to Pylex at the label-recommended rate only. Moderate tolerance (21% to 35% injury) was observed with buffalograss receiving Pylex at label rate and with both little bluestem and purple lovegrass receiving twice the label-recommended rate (Figure 3). Prairie dropseed, sideoats grama and switchgrass were severely injured in both years when Pylex was applied at either rate.

Take-home message

Results from this experiment not only build upon past research involving the studied grass species or herbicides (2, 6, 7, 9), but also provide novel information on the tolerance of these 11 grass species to the examined herbicides and rates, particularly for broomsedge bluestem, buffalograss, indiangrass, little bluestem, prairie dropseed, purple lovegrass and sideoats grama, for which these herbicides and rates had not been previously investigated.

As expected, results demonstrate that species tolerate herbicides and rates differently. Drive XLR8 (quinclorac) applied once at the label rate of 4 pints/acre (4.68 liters/hectare) was the only herbicide treatment that provided acceptable injury (<20%) on all 11 species. With the exception of strong creeping red fescue, Segment II (sethoxydim) significantly injured all other grass species. Furthermore, strong creeping red fescue was the only species tested that appeared to be tolerant to all three herbicides and rates in this experiment, which may suggest this species should continue to be used in minimal- to no-mow areas. Injury from Pylex (topramezone) varied among grass species and herbicide rates.

While our experiment investigated the tolerance of the grass species receiving only one application, which is typical of minimal- to no-mow areas, golf course superintendents should be cautious when conducting sequential applications during the same growing season, as this could increase injury on the desirable grasses.

Regardless, additional research is needed on the tolerance of grass species to subsequent applications of these herbicides for weeds that are more difficult to control.

Biodiversity of grass species in minimal- to no-mow golf course rough areas may help promote ecological sustainability and enhance aesthetics on golf courses by using species with varying abiotic and biotic stress tolerances. This research highlights the importance of identifying and understanding the composition of grass species in polycultures being maintained as minimal- to no-mow golf course rough. More specifically, by understanding the grass species present in managed areas, golf course superintendents can then reduce the likelihood of injury by selecting the herbicide and rate that is safest for the entirety or majority of plant species present in the area or by using spot treatments to avoid applications on sensitive species.

Golf course superintendents who need to control weeds — especially with broadcast applications — in minimal- to no-mow areas should first identify the species and their significance in the area prior to herbicide selection and application.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the funding support by BASF. We thank personnel at the W.H. Daniel Turfgrass Research and Diagnostic Center for their efforts in this research. The full manuscript of the experiment is available in Agrosystems, Geosciences & Environment (https://doi.org/10.1002/agg2.20204).

The research says ...

- All 11 grass species were tolerant to Drive XLR8 (quinclorac) applied at label rate.

- Segment II (sethoxydim) significantly injured 10 of 11 grass species.

- Strong creeping red fescue, which had <5% injury from all three herbicides, exhibited the greatest tolerance among grass species tested.

- Injury from Pylex (topramezone) varied among grass species and herbicide rates.

- Because there are herbicide tolerance differences among grass species, golf course superintendents should identify desired grass species prior to herbicide selection and application.

Literature cited

- Braun, R.C., A.J. Patton, E. Watkins, P. Koch, N.P. Anderson, S.A. Bonos and L.A. Brilman. 2020. Fine fescues: A review of the species, their improvement, production, establishment, and management. Crop Science 60(3):1142-1187 (https://doi.org/10.1002/csc2.20122).

- Butler, J.H.B., and A.P. Appleby. 1986. Tolerance of red fescue (Festuca rubra) and bentgrass (Agrostis spp.) to sethoxydim. Weed Science 34(3):457-461.

- Colding, J., and C. Folke. 2009. The role of golf courses in biodiversity conservation and ecosystem management. Ecosystems 12:191-206 (https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-008-9217-1).

- Dobbs, E.K., and D.A. Potter. 2015. Forging natural links with golf courses for pollinator-related conservation, outreach, teaching, and research. American Entomologist 61(2):116-123 (https://doi.org/10.1093/ae/tmv021).

- Gelernter, W.D., L.J. Stowell, M.E. Johnson and C.D. Brown. 2017. Documenting trends in land-use characteristics and environmental stewardship programs on U.S. golf courses. Crop, Forage & Turfgrass Management 3:1-12 (https://doi.org/10.2134/cftm2016.10.0066).

- Johnston, C.R., J. Yu and P.E. McCullough 2016. Creeping bentgrass, perennial ryegrass, and tall fescue tolerance to topramezone during establishment. Weed Technology 30(1):35-44 (https://doi.org/10.1614/WT-D-15-00072.1).

- Marble, S.C., M.T. Elmore and J.T. Brosnan. 2018. Tolerance of native and ornamental grasses to over-the-top applications of topramezone herbicide. HortScience 53(6):842-849 (https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI12989-18).

- Nelson, M. 1997. Natural areas. United States Golf Association Green Section Record, November/December:7-11.

- Tallarico, J., and T. Voigt. 2004. Weed control in ornamental grasses. Golf Course Management 72(2):143-147.

- Voigt, T., and J. Tallarico. 2004. Turf and native grasses for out-of-play areas. Golf Course Management 72(3):109-113.

Aaron J. Patton is a professor and Ross C. Braun is a lead research scholar in the Department of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture at Purdue University, West Lafayette, Ind.