Seedheads in annual bluegrass greens reduce putting speed, consistency, playability and aesthetics. Photo by Zac Reicher/Bayer

Editor’s note: This research was funded by the United States Golf Association.

Annual bluegrass (Poa annua L.) seedhead production on putting greens results in a number of detrimental effects, including but not limited to reduced putting speed and consistency and compromised aesthetics (2, 3, 6). To provide a more consistent putting surface, golf course superintendents have used a number of cultural practices, such as verticutting, the application of herbicides to reduce annual bluegrass populations, and plant growth regulators to suppress seedhead flushes (8).

Research and repeated golf course applications over many years have shown that plant growth regulators such as Embark (mefluidide) and Proxy (ethephon, Bayer) provide the best reduction in seedhead production (1, 4, 5). After phytotoxicity was associated with Embark, it was taken off the market, leaving Proxy as the only plant growth regulator available for suppression of annual bluegrass seedhead production (6, 7). However, reports from golf course superintendents indicate that seedhead suppression with Proxy in the field has been inconsistent.

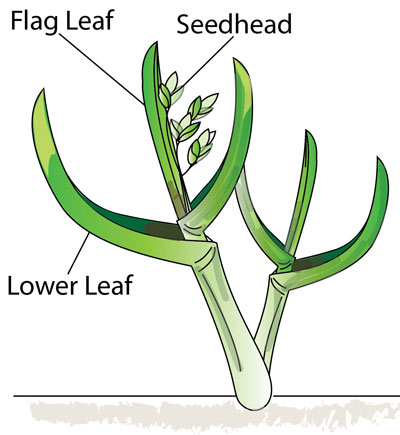

Recent research (7) has determined that Proxy absorption and transportation from the flag leaf — or uppermost leaf of the culm, which encloses the seedhead during the boot stage — contribute to seedhead suppression more than absorption and transportation from the lower leaves. However, mowing, a critical practice on golf course putting greens, removes the flag leaf. Therefore, the research (7) would suggest that mowing before Proxy application would prevent optimal absorption, and that mowing following application would prevent optimal transportation of the plant growth regulator.

Right: In annual bluegrass, Proxy absorption and transportation from the flag leaf has been shown to contribute more to seedhead suppression than the same activity by lower leaves of the plant. Illustration by Alec Kowalewski

When considering these recommendations and the importance of frequent mowing in relation to putting green performance, the current quandary facing turfgrass managers is how long to delay mowing before and after Proxy applications for maximum seedhead suppression. Therefore, the objective of this research was to determine whether mowing delays before and after the application of Proxy affect the seedhead suppression of annual bluegrass during the spring flush.

Materials and methods

Field research was conducted on an annual bluegrass putting green vegetatively established in 2004 at the Lewis-Brown Turf Farm in Corvallis, Ore., on a 12-inch (30.48-centimeter) layer of sand meeting USGA recommendations for putting green construction.

For all treatments, Proxy was applied at a rate of 5.0 fluid ounces/1,000 square feet (1.59 milliliters/square meter). Seedhead counts were done using a small piece of plywood with a circular cutout 4.0 inches (10.16 centimeters) in diameter. The plywood was gently tossed on the plots three times, and the seedheads showing in the hole were counted. The three subsamples were then averaged.

The putting green used for this research was mowed with a Jacobsen Eclipse walk-behind mower at 0.125 inch (3.175 millimeters) with clippings collected. The green received fertilizer applications every other week in the summer months and monthly in fall and spring (total 4.5 pounds nitrogen/1,000 square feet [219.70 kilograms/hectare] annually). Primo MAXX (trinexapac-ethyl, Syngenta) was applied alone throughout the growing season at a rate of 0.1 fluid ounce/1,000 square feet (0.318 liter/hectare) every two weeks. The experimental area was aerified every spring and fall with a John Deere Aercore 800 — 2- × 2-inch (5- × 5-centimeter) spacing with 0.5-inch (1.27-centimeter) (inside diameter) hollow tines. Light and frequent sand topdressing applications were applied to the green throughout the growing season. Irrigation and hand watering were applied as needed during the summer months to provide healthy annual bluegrass.

Results

Year 1: Mowing 1 to 3 days before Proxy application

In 2015, the experimental design was a 4 × 3 factorial, randomized complete block with four replications. Factors included delaying mowing before Proxy application (mowing the day of application as well as mowing 1, 2 and 3 days before application) and delaying mowing following Proxy application (delaying mowing until 1, 2 and 3 days after application) (Table 1). Mowing delays of 1 to 3 days before and after Proxy application did not significantly affect annual bluegrass seedhead production.

Year 2: Mowing 3 to 12 days before Proxy application

Because statistical differences were lacking in the 2015 results, the experimental design was adjusted in 2016 to a one-way treatment structure containing six treatments and arranged in a randomized complete block design with four replications. The objective of this experimental design was to explore a greater duration of mowing delay before Proxy application (mowing the day of application as well as a 3-, 6-, 9- and 12-day delay) and a control treatment without Proxy application (Table 2).

This greater duration of mowing delay before application was investigated to possibly allow the flag leaf to mature more fully. However, our results revealed that mowing delays of 3 to 12 days before Proxy application did not affect annual bluegrass seedhead production. In contrast, on June 7, 2016 (3 weeks after Proxy application), all treatments that received Proxy had fewer seedheads than the untreated control.

Year 3: Mowing 1 to 24 hours after Proxy application

Because differences in mowing delay before application (1 to 3 days in 2015, and 3 to 12 days in 2016) were not significant, in 2017, the experimental design was adjusted to explore short mowing delays after Proxy application (1-, 2-, 3-, 4-, 6-, 8- and 24-hour delays), and a control treatment without Proxy was included in this study (Table 3).

A mowing delay of 2 to 24 hours had no effect on Proxy seedhead suppression when compared with an untreated control (center plot) observed on May 31, 2017 (3 weeks after application), in Corvallis, Ore. Photo by Brian McDonald

Three weeks after application, all treatments that had been treated with Proxy, regardless of the mowing delay, had fewer seedheads than the untreated control. Five weeks after Proxy application, the treatment with a 1-hour mowing delay after Proxy application had seedhead counts comparable to those of the untreated control. A mowing delay of 2 to 24 hours did not reduce the effects of Proxy application. Findings suggest that delaying mowing for 2 hours after Proxy application will give the product sufficient time to be absorbed by annual bluegrass in the western Oregon climate.

Conclusion

Findings from this work conclude that mowing just before Proxy application does not affect product efficiency. A mowing delay of 1 hour after Proxy application was the only treatment that reduced the product’s ability to suppress seedhead production. The current Proxy label states, “For maximum performance, delay mowing until the day after application,” but findings from this research suggest a mowing delay of 2 hours is adequate.

Funding

Funding for this research was provided by the United States Golf Association.

The research says ...

- Researchers hypothesized that delaying mowing before or after the application of Proxy to annual bluegrass greens would make the product more effective at suppressing Poa annua seedhead production.

- All mowing delays (1 to 3 days and 3 to 12 days) before Proxy application had no effect on seedhead production of Poa annua.

- A 2-hour delay after Proxy application effectively reduced seedhead counts. The current Proxy label states that, for best results, mowing should be delayed until the day after product application.

Literature cited

- Askew, S.D. 2017. Plant growth regulators applied in winter improve annual bluegrass (Poa annua) seedhead suppression on golf greens. Weed Technology 31:701-713.

- Cook, T. 2008. Annual bluegrass, Poa annua L. Department of Horticulture, Oregon State University. (https://agsci.oregonstate.edu/beaverturf/annual-bluegrass-poa-annua-l) Accessed Sept. 29, 2019.

- Cooper, R.J., P.R. Henderlong, J.R. Street and K.J. Karnok. 1987. Root growth, seedhead production, and quality of annual bluegrass as affected by mefluidide and a wetting agent. Agronomy Journal 79:929-934.

- Haguewood J.B., E. Song, R.J. Smeda, J.Q. Moss and X. Xiong. 2013. Suppression of annual bluegrass seedheads with mefluidide, ethephon, and ethephon plus trinexapac-ethyl on creeping bentgrass greens. Agronomy Journal 105:1832-1838.

- Inguagiato J.C., J.A. Murphy and B.B. Clark. 2010. Anthracnose development on annual bluegrass affected by seedhead and vegetative growth regulators. Applied Turfgrass Science doi:10.1094/ATS-2010-0923-01-RS

- Kane, R., and L. Miller. 2003. Field testing plant growth regulators and wetting agents for seedhead suppression of annual bluegrass. USGA Turfgrass and Environmental Research Online 2(7):1-7.

- McCullough, P.E., and S.S. Sidhu. 2014. Ethephon absorption and transport associated with annual bluegrass inflorescence suppression. Crop Science 54:845-850.

- Patton, A.J., R.C. Braun, G.P. Schortgen, D.V. Weisenberger, B.E. Branham, W. Sharp, M.D. Sousek, R.E. Gaussoin and Z.J. Reicher. 2019. Long-term efficacy of annual bluegrass control strategies on golf course putting greens. Crop, Forage and Turfgrass Management 5:180068. doi:10.2134/cftm2018.09.0068

Brian McDonald is a senior faculty research assistant, and Alec Kowalewski is an associate professor in the Department of Horticulture at Oregon State University, Corvallis, Ore. Conner Olsen is an assistant superintendent at Oswego Lake Country Club in Lake Oswego, Ore., and a four-year member of GCSAA.