Many fine golf courses have not changed much since they were built more than 50 years ago. Renovating putting greens by installing a new, improved creeping bentgrass and adding new drainage systems to ensure the health and quality of the playing surface should improve player satisfaction and, over time, reduce the need for intensive turf management. Photo by Dan Dingman

This article is an open letter providing ideas and recommendations to superintendents who are passionate about providing top-quality course conditions but are novices at putting green regrassing and renovation and have greens that need serious help.

The golf course superintendent’s job is to provide the best playing conditions with the given resources and environment. The resources include budgetary items such as labor, equipment, the irrigation system, etc., and the environment encompasses the soil, vegetation and climate. Playing conditions are limited by resources and/or environment. A golf course renovation is an opportunity to mitigate environmental limitations — to remove limitations caused by excessive moisture, temperature, shade and/or humidity. A successful renovation should allow a superintendent to use resources more efficiently throughout the golf course (8).

Improving putting greens

The courses discussed here have greens that are typical of cool, humid zones and that have lasted 50 to 100 years or more. They have a significant surface slope, and, over the past 15 to 40 years, they have been treated with an aggressive, consistent topdressing program. This smooth surface and mowing technology have allowed for the reduction of cutting heights from 0.16 inch (4.06 mm) in 1990 to 0.10 inch (2.54 mm) today, all with the same plant.

Your greens are as good as cultural practices allow and, frankly, are as good as the weather. What they are missing — and what renovations are all about — is a grass that has been bred to thrive (not adapt) in a putting green situation and a construction system that removes the environment (that is, moisture) from the equation.

This putting green situation is not unusual. You have provided excellent playing conditions — in many respects, better than those of your competitors. The issue is that, as other courses add new grasses and construction technology, your course starts to lag because cultural practices alone cannot match their upgrades. The more renovations your members experience at other courses, the more they will note the absence of improvements to your greens. It will not get better.

Greens in this climate are a mixture of creeping bentgrass (Agrostis palustris) and annual bluegrass (Poa annua var. reptans). The creeping bentgrass varieties are typically older and have likely been in place for 50 years or longer. The annual bluegrasses are naturally occurring botanical varieties that have adapted to the environmental and cultural conditions of the putting surface. Rarely is there a monostand of older creeping bentgrass, but there are certainly plenty of examples of extensive stands of annual bluegrass.

Creeping bentgrass — especially the newer varieties — performs better than annual bluegrass with less water and fewer chemicals. Annual bluegrass has a fine leaf texture and provides an excellent putting surface when environmental conditions are favorable. For this reason, it may be cultivated and tolerated on putting greens despite its need for extensive inputs.

Fifteen years ago, before the latest round of creeping bentgrass breeding advancements, annual bluegrass provided the best putting surface when conditions were right. Because they survive a similar height of cut, the newer bentgrasses that became available around 2010 are equal to or better than annual bluegrass, and they certainly provide excellent putting surfaces throughout a wider range of seasonal and climatic factors with far fewer chemical inputs (10). The new varieties have a finer leaf blade compared with older creeping bentgrasses. The wider leaf blade of the older creeping bentgrasses is a genetic function that cultural practices cannot change.

The newer creeping bentgrass varieties can provide an exceptional putting surface throughout the season — not just when climatic conditions are favorable. Greenkeepers can do this with fewer inputs (multiple mowing/rolling), and the putting surface/grass suffers less stress throughout the season. The new creeping bentgrass varieties are finer-textured (narrow leaf width) and denser, have an upright growth habit (the preferred qualities of annual bluegrass), and also have outstanding heat, cold and wear tolerance and recuperative ability, as do all creeping bentgrass varieties. The turfgrass breeders have done their jobs.

Putting green renovation requirements

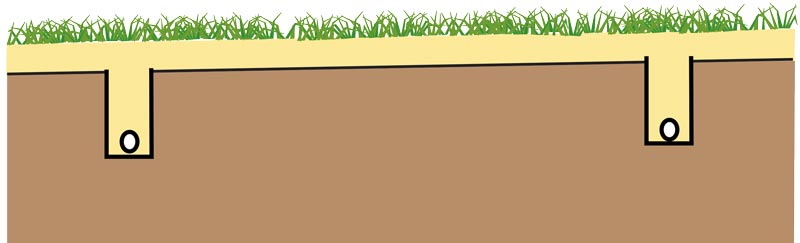

Figure 1. In order to grow and maintain creeping bentgrass varieties and minimize annual bluegrass invasion, the putting green site must have a drainage system (natural drainage is rarely significant enough) and be shade-free (morning shade at the very least). Illustration by Alec Kowalewski

Drainage

In order to grow and maintain creeping bentgrass varieties and minimize annual bluegrass invasion, the putting green site must have a drainage system (natural drainage is rarely significant enough) and be shade-free (morning shade at the very least) (Figure 1). Significant compromise on either factor will ultimately lead to failure of the renovation — or, at the very least, unrealized potential.

Creeping bentgrass prefers well-drained conditions. For a putting green, this means either installing tile drainage in existing greens or constructing greens with sand-based root zones. If sand-based greens already exist and function properly, then few modifications are necessary. If the greens were originally push-up greens that were built with on-site native soil and then sand-topdressed, internal drainage must be addressed.

The first option is to install specifically oriented drain tile throughout the green site and approach. This process is not new; it has been around for more than a century. However, as the renovation boom has evolved and the need for drainage of these aging sand-topdressed greens has become evident, a cottage industry has emerged, with companies that can efficiently and neatly install drainage with minimal disruption to the green surface. Examples of companies that provide this service are XGD, Golf Preservations and EXtreme Drainage. Each company in this line spun off from the first — a true sign of a good idea and an opportunity. There are likely others.

The advantage of this tile system is ease of installation and lack of disruption (7). It also preserves surface contours. The grass conversion can follow the tile installation, but not vice versa. The excess moisture travels through the sand topdressing layer to the nearest drain line (often 6-foot spacing). It is very effective.

Drain tile can be installed neatly and efficiently with minimal disruption of the green surface. Photos by Travis Fox

The disadvantage of this system is that bad or poorly contoured greens are not changed, and the green surface cannot dry down evenly. The idea is that consistent moisture across a green surface affects playability and maintenance. Peaks, knobs and high spots on greens will get drier, faster; low spots — usually the fronts of greens — will be the wettest. Because the low spot is the green front, playability is often negatively affected (4,9). Although drainage installation makes a better green — often bordering on tremendously better — it does not make the best green.

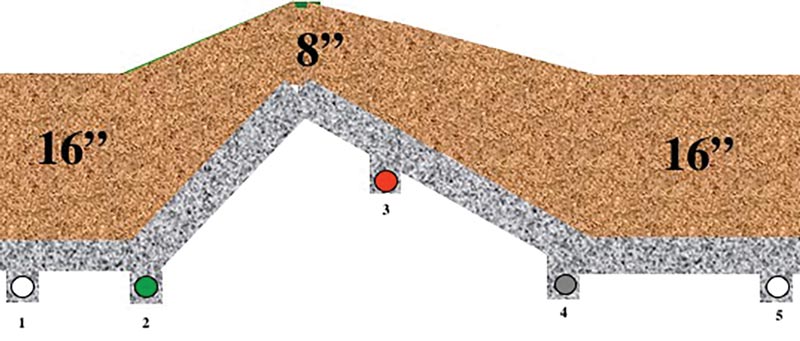

Beginning in 1960, the USGA produced a pamphlet that provided specifications for sand-based putting green construction. This design is a 12-inch (30.48-cm) root-zone profile over a 4-inch (10.16-cm) gravel drainage blanket, with drain pipes for excess water. Several edits, most recently in 2018, have improved this construction method.

The latest, most significant change is to vary the depth of the profile depending on green elevation and slope (12). High areas have shallower profiles so they don’t dry out, and low areas are deeper to keep the surface drier. This keeps playability and maintenance optimal.

After 2010, the advent of GPS and lasers made it possible to construct greens with variable depths easily, and the overall cost is negligible compared with the costs of traditional construction methods. Several courses have employed this technique since 2014, including Baltimore Country Club, Moraine Country Club (Dayton, Ohio), Meadowbrook Country Club (Detroit) and Winged Foot Golf Club (Mamaroneck, N.Y.).

The disadvantages of this system are a slight increase in cost and course closure during reconstruction, as the root-zone depth of the green cannot be increased without demolishing the green.

Figure 2. These illustrations show the USGA putting green profile with standard root-zone depth (top) and with varied root-zone depth. Illustrations by Kevin Frank

Shade

The second environmental concern is shade. Shade is usually caused by trees, and tree removal in the southeast quadrant of the green site is imperative. This guideline has few, and minuscule, exceptions. Creeping bentgrass will not survive in shaded areas (1). If shade is not addressed, these areas will, over time, convert to either an annual bluegrass stand or to bare ground (or both). The southeast quadrant is critical because of the angle of the sun.

Furthermore, investigations have proved the critical times for creeping bentgrass growth and subsequent annual bluegrass invasion are the shoulder seasons, March/April and October/November. The angle of the sun is low at these times, and shade from trees in the southeast quadrant can last well into the late morning and even early afternoon. Total light can be quite low during this time even though the plant light requirements are the same as those of a late spring/early summer day when the day is longest.

Greens renovation procedures

The renovation process is the most painful aspect of the project. Besides the closure of the golf course, there are construction costs and lost revenue from all operations. All of our research efforts since 2011 have focused on minimizing course closure time while ensuring a sustainable product upon course reopening. What was thought of as a five- to eight-month closure period is now a 75- to 90-day establishment period, thanks to better understanding of fertilizer, mowing, brushing and topdressing procedures during establishment. The establishment procedure is significantly different from maintenance and often something that is foreign to the superintendent.

In the northern tier of golf courses, the start time for a procedure is usually sometime in August, with a reopening the next May or June. The 75- to 90-day establishment rule is in play here, but the number is split in some fashion by the winter season. The day of seeding dictates the day of opening, but so do the onset of winter and the beginning of spring.

The best thing about the renovation is the creeping bentgrass itself. Summer is the best period for creeping bentgrass in northern climates. The recuperative ability of the plant is highest in summer, making it easier to use the golf course after it reopens for that first season (5). By contrast, Florida bermudagrass renovations are the exact opposite, as the bermudagrass established in summer is now growing at its lowest rate in December/January and must persist through tremendous use with high expectations and little to no growth/recovery.

Another component of renovation is the green construction technique, which can entail simply applying a soil sterilant to existing greens — assuming drainage is adequate — and then seeding into the mat layer (2), or can require a complete reconstruction of green sites and surrounds. For the latter, the construction time depends on the labor on the site. Increased labor means increased costs but also a shorter construction period and a quicker return to the golf course following establishment. Clearly, this involves advance planning by the superintendent and the club, and reservations for work crews must be made months or years in advance, particularly now, when so many courses are undergoing renovations.

Interseeding

Two common questions that arise during renovation discussions involve either seeding into existing greens to change species or sodding greens after surface preparation. Both of these approaches are attempts to avoid shutting down the golf course or, at the very least, to shorten the shutdown.

In the case of interseeding bentgrass, there have been numerous studies and anecdotal evidence of efforts to determine an appropriate conversion method. To date, no research has shown that interseeding is an effective method of species conversion. Most results show no increase or increases of 1% to 2% over a two-year trial period (3,11). It can be argued that continuing interseeding for five years or more could result in exponential increases in a turf species, but even then, the time frame is lengthy and the conversion is far from complete.

Reasons for the lack of success revolve around competition and establishment. The competition between the new seedlings and mature plants — and any other seed, such as annual bluegrass — is disadvantageous to the seedling in terms of water and nutrient availability. Combine this with a daily mowing height designed for a mature turfgrass stand, and the reasons for failure become clear.

Sodding

Sodding greens with creeping bentgrass is also an option, but you cannot broach this subject without forethought. For every sodding success, there is a sodding failure. Instant green does not mean instant playing quality, and superintendents should not count on anything beyond adequate playing quality during the first year.

The first issue to consider is the quality of the sod to be installed. The soil harvested with the sod must be compatible with the existing root zone of the greens. Anything short of this will require core cultivation beyond normal procedures for three to four years (6). The sod may be washed free of any soil before it comes to the course, but the sod farm must be capable of carrying out this procedure (most are not), and the sod will require significant time for new root establishment, as all of the roots will have been washed off before sod installation. Therefore, golfer expectations should be even lower.

Installing new sod can be a faster and more effective way of replacing the existing turf if the quality, age and condition of the sod are optimal and the soil harvested with the sod is compatible with the root zone of the existing green. Photos by J.N. Rogers

Another quality factor is age/condition of sod — primarily the condition of the thatch/mat layer. The mat layer on a putting green is modified with sand topdressing to provide a smooth surface. The sod farm may have topdressed — again, the material needs to be compatible — but often this has not been done, and the superintendent is expected to topdress the sod. This is not a problem, but it may take up to six months — the majority of the first growing season — to modify the mat layer. The key here is to avoid raising member expectations that first year if the green is resodded.

Can there be an exception with sod? Sure. If the sod is grown either on your golf course or on a sod farm, so that the mat layer is continually modified with a sand topdressing and there is soil compatibility, then sodding can decrease the total number of days closed and even shorten the return to good playing conditions. However, it is easy to see that these caveats require time to prepare and extended periods in which resources are dedicated to intensive turf management.

While the golf course is closed

If the golf course is closed to establish grass on putting greens, that period will be a minimum of 75 to 90 days. Assuming approaches and collars are already in the conversion, this is an excellent time to convert tees and fairways to creeping bentgrass as well. Neither area takes as long to establish as the putting green, and, although the same drainage and sunlight guidelines apply, these areas are not under the same stress from low mowing heights and can be opened with little trepidation.

In areas under severe weed contamination, a soil sterilant is an option. Other than the cost of sterilant, the cost of the seed, fertilizer and herbicides will likely equal the cost of plant protectants applied to unrenovated turf during that time — resulting in a wash in terms of cost, if you will.

In summary, I hope this letter begins to answer the questions around renovation. I stand ready to answer any questions from superintendents or their committees.

Funding

Funding was provided by the Michigan Turfgrass Foundation and MSU AgBio Research.

Acknowledgment

I would like to acknowledge graduate assistants Thomas Green, Eric Chestnut, Jacob Bravo and Ryan Bearss for their contributions.

The research says ...

- Renovating aging greens is imperative for golf courses that want to remain competitive.

- Older greens are typically a mix of creeping bentgrass and annual bluegrass, and converting greens to an improved creeping bentgrass variety creates a more attractive, better-quality putting surface that requires fewer inputs.

- Drainage and shade are the primary problems that need to be addressed before the green can be regrassed.

- Although sodding can be an option — technology has improved the process — seeding is still a far better choice.

- The period during the greens conversion is also an ideal time to convert tees and fairways.

Literature cited

- Bell, G.E., T.K. Danneberger and M.J. McMahon. 2000. Spectral irradiance available for turfgrass growth in sun and shade. Crop Science 40:189-195.

- Bravo, J.S., T.O. Green, J.R. Crum, J.N. Rogers III, S. Kravchenko and C.A. Silcox. 2018. Evaluating the efficacy of dazomet for the control of annual bluegrass seed germination in renovated turf surfaces. HortTechnology 28(1):44-47.

- Cattani, D.J. 2001. Effect of turf competition on creeping bentgrass seedling establishment. International Turfgrass Society Research Journal 9(2):850-854.

- Frank, K.W., B.E. Leach, J.R. Crum, P.E. Rieke, B.R. Leinauer, T.A. Nikolai and R.N. Calhoun. 2005. The effects of a variable depth root zone on soil moisture in a sloped USGA putting green. International Turfgrass Society Research Journal 10(2):1060-1066.

- Green, T.O., E.C. Chestnut, J.R. Crum and J.N. Rogers III. 2018. Effects of creeping bentgrass seeding rates and traffic on putting green establishment. Golf Course Management 86(1):100-104.

- Kowalewski, A.R., J.N. Rogers III and T.D. VanLoo. 2008. Pre-harvest core cultivation of sod provides alternative cultivation timing. Applied Turfgrass Science 5(1):1-10.

- Kowalewski, A.R., J.R. Crum, J.N. Rogers III and J.C. Dunne. 2011. Improving native soil athletic fields with intercept drain tile installation and subsequent sand topdressing applications. Soil Science 176(3):1-7.

- O’Brien, P., and D.A. Oatis. 2018. Successful putting green construction starts with planning. USGA Green Section Record 56(5):1-6.

- Prettyman, G.W., and E.L. McCoy. 2003. Profile layering, root zone permeability, and slope affect on soil water content during putting green drainage. Crop Science 43:985-994.

- Rana, S.S., and S.D. Askew. 2018. Measuring canopy anomaly influence on golf putt kinematics: Does annual bluegrass influence ball roll behavior? Crop Science 58:911-916.

- Sweeney, P., and K. Danneberger. 1998. Introducing a new creeping bentgrass cultivar through interseeding: Does it work? USGA Green Section Record 36(5):19-20.

- United States Golf Association. 2018. USGA recommendations for a method of putting green construction. Far Hills, N.J.

John N. Rogers III, Ph.D., is a professor and coordinator of golf turf and sports turf management programs in the Department of Plant, Soil and Microbial Sciences at Michigan State University, East Lansing, Mich. In addition to conducting renovation research, he has assisted on more than 12 renovations in five U.S. states.