The site for this research was a Diamond zoysiagrass nursery green at Clemson University’s Walker Golf Course in Clemson, S.C. Photos by Josh Weaver

Thatch is a layer of living and dead plant material (mostly shoots, stems and roots) between turfgrass leaf tissue and the soil surface (3). Moderate levels of thatch provide desirable surface resiliency and nutrient retention, but excessive levels can decrease playability of turf surfaces, increase disease pressure and mower scalping, and reduce pesticide efficacy and water infiltration (4). In a high-maintenance turf setting such as a golf green, plant tissue is often produced faster than it is decomposed, resulting in thatch accumulation.

In recent years, considerable attention has been focused on controlling thatch/organic material buildup in golf greens without using traditional methods such as aerification, verticutting, grooming and topdressing, which disrupt play. Previous studies have investigated biological thatch control options such as biostimulants, which are organic materials that, when applied in small quantities, enhance plant growth and development (6). Most biostimulants contain an array of sucrose, glucose or other sugar sources; plant nutrients at low rates; and various acids, wetting agents/surfactants and inoculated microorganisms (5).

The objective of this research was to evaluate two biostimulant products, Worm Power Turf and EarthMax, and their impacts on thatch and rooting depth. In addition to the biostimulants, two industry standards, blackstrap molasses and sand topdressing, were included in the research.

Materials and methods

Two 16-week field studies were conducted from May to September 2018 and replicated from May to September 2019 on a Diamond zoysiagrass [Zoysia matrella (L.) Merr.] nursery green at the Walker Golf Course at Clemson University in Clemson, S.C. The same location on the nursery green was used in both years of the study. The objectives of this study were to measure surface firmness within the treated areas and to determine the effects of biostimulants and cultural practices on turfgrass rooting length and mass, turfgrass thatch thickness and weight, turf quality, and normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI).

The zoysiagrass green was established in June 2013 via sod in a former creeping bentgrass green constructed with USGA soil mix in 1995. The experiment was arranged with 6.5- × 9.8-foot (2- × 3-meter) plots as a randomized complete block design with four replicates.

Treatments were applied using a pressurized CO2 backpack boom sprayer with a carrier volume of 20.3 gallons/acre (190 liters/hectare) through TeeJet 8003 flat-fan nozzles. Treatments and application frequencies are presented in Table 1. Maintenance overhead irrigation equivalent to 0.5 inch (1.25 centimeters) was applied as needed, but all treatments were watered immediately after application with this rate.

Plots were mowed daily by Walker Golf Course staff from 0.1 to 0.125 inch (2.54 to 3.175 millimeters). Solid-tine aerification, vertical mower grooming and topdressing were all performed uniformly throughout the study. Core aeration was performed using 1.27-centimeter tines with 1- × 1-inch (2.54- × 2.54-centimeter) spacing on June 25, 2018, and June 21, 2019.

Fertilization was applied via foliar application equivalent to 32.1 ounces nitrogen/1,000 square feet (9.8 grams/square meter) per month during rating dates. Fall fungicide applications were applied uniformly across plots, but no additional biostimulant products were applied by the golf course staff.

Application rates for the two biostimulants, Worm Power Turf (Aqua-Aid Solutions) and EarthMax (Harrell’s), were taken from product labels (see Table 1). Rates for the molasses treatment, a commercial formulation of blackstrap molasses (The Plant Food Co.), and sand topdressing are also shown in Table 1.

Measurements

Treatment effects were assessed by measuring turf quality, normalized difference vegetation index, surface firmness, turfgrass rooting length, rooting weight, thatch thickness and thatch weight.

Turf quality ratings included color, density and vigor (2). No statistical differences were found among any treatments for turf quality, NDVI or surface firmness in either year of the study, and all treatments provided satisfactory turf (data not shown).

At study initiation and completion, thatch thickness (the distance between living green tissue and soil surface) was measured with a ruler in millimeters. At study completion, rooting mass measurements were taken. Roots were washed to remove soil, dried at 80 degrees C for 72 hours (1), weighed, and then ashed in a muffle furnace for three hours at 550 degrees C. Remaining contents were reweighed. Total rooting weight was the difference between the weight of the oven-dried roots and the ashed roots. Determined by the same method, thatch weight was the difference between the weight of the oven-dried thatch and the ashed thatch.

Results and discussion

Products were evaluated for their ability to increase root length and weight and decrease thatch weight and thickness.

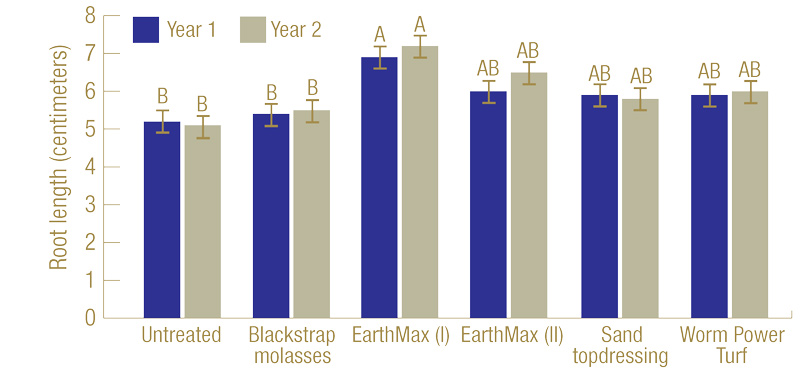

Figure 1. Turfgrass rooting length for two 16-week thatch control field studies at the Walker Golf Course at Clemson University. Means followed by the same letter are not significantly different.

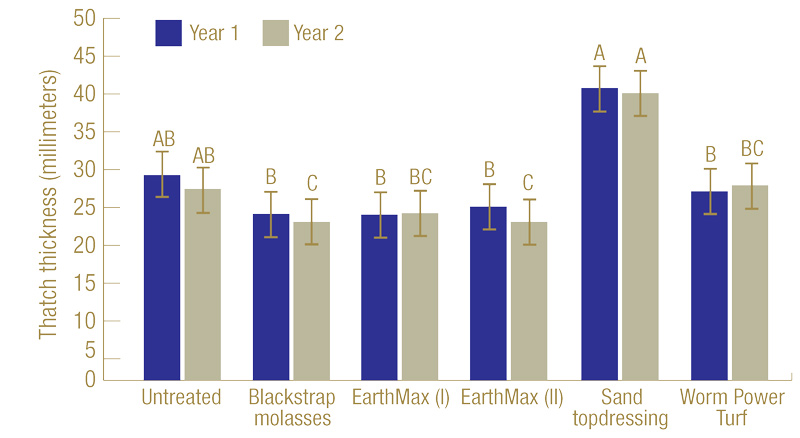

Figure 2. Turfgrass thatch thickness for two 16-week thatch control field studies at the Walker Golf Course at Clemson University. Means followed by the same letter are not significantly different.

Root length. In year one, EarthMax (I) increased root length ≥28% over blackstrap molasses and the untreated control. This also held true in year two, as EarthMax (I) provided ≥30% greater root length than blackstrap molasses and the untreated control. No other differences were observed between treatments (Figure 1, Table 2).

Root weight. In year one, treatment with blackstrap molasses resulted in a 501% increase in root weight compared with the untreated control. Blackstrap molasses also provided root weight ≥133% greater than all other treatments. No other differences were observed between treatments. In year two, blackstrap molasses provided an increase in root weight ≥529% greater than the untreated control and sand topdressing. In contrast, Worm Power Turf, EarthMax (I) and EarthMax (II) resulted in root weight ≥97% greater than the untreated control and sand topdressing (Table 2).

Click on image to enlarge:

In comparison with the untreated control, Worm Power Turf, EarthMax and sand topdressing provided an average 18% greater rooting length. EarthMax reduced thatch thickness by an average of 29%, blackstrap molasses did so by 30%, and Worm Power Turf did so by 17%.

Thatch weight. In year one, all treatments were statistically similar in thatch weight compared with the untreated control, but differences were observed between treated plots. Treatments of Worm Power Turf and EarthMax (I) resulted in ≥16% greater thatch weight than treatment with blackstrap molasses. In year two, Worm Power Turf and sand topdressing provided ≥29% greater thatch weight than blackstrap molasses. Thus, blackstrap molasses provided statistically lower thatch weight than Worm Power Turf in both years. As in year one, there were no statistical differences between treated plots and the untreated control in year two (Table 2).

Thatch thickness. In year one, as with thatch weights, no differences were observed between the treatments and the untreated control. Sand topdressing provided ≥53% greater thatch thickness than all other treated plots. At the completion of year two, the untreated plots provided ≥42% greater thatch thickness than EarthMax (II) and blackstrap molasses (Figure 2). No other treatments provided differences from the untreated control. Overall, sand topdressing provided ≥48% greater thatch thickness than all other treated plots in both years of the study (Figure 2, Table 2).

Conclusions

Data from this two-year study warrants further investigation of both biostimulants (Worm Power Turf and EarthMax) and sand topdressing and their effects on rooting length. In addition, Worm Power Turf, EarthMax and blackstrap molasses should be examined further in regard to rooting weight, because those treatments resulted in greater rooting weight than the untreated control. Blackstrap molasses did so in both years, whereas the biostimulants only did so in year two. All treatments for thatch weight produced results similar to those of the untreated control, but blackstrap molasses performed better than a number of other treatments. In year two, blackstrap molasses and EarthMax (II) showed a reduction in thatch depth compared with the untreated control.

An interesting observation from this study is that blackstrap molasses provided the greatest root weight in both years, but was one of the statistically lowest in root length. This indicated roots being generated in plots treated with blackstrap molasses were growing abundantly but were not growing to a great depth. Furthermore, blackstrap molasses was among the treatments producing the lowest values in both thatch weight and thickness. This indicates increased root mass was not added to the thatch. Thus, blackstrap molasses presents a potentially cost-effective biostimulant for golf course putting green use. This could prove significant, as zoysiagrass contains more lignin than most turfgrasses, and lignin contains phenolic and alcoholic characteristics that are resistant to decomposition by soil organisms (3). Turfgrasses containing less lignin theoretically could experience greater thatch reduction with these and similar materials.

From the second author’s years of experience, turfgrasses grown in sand-based soils typically respond more positively to biostimulant use than those grown in heavier soils. Sandy soils generally have a low cation exchange capacity (CEC), which can be increased by humic and/or fulvic acids, a major component of most biostimulants. To be effective, biostimulants typically must be applied in more than one growing season, because they generally stimulate soil microorganisms that require an extended time to naturally decompose excessive thatch, especially thatch containing higher levels of lignin.

Future research should build on data from the current study by examining different turfgrass types, rates and soil profiles and other cultural practices, such as various aerification and verticutting schedules.

Funding

This research was funded through Bert McCarty’s lab and was completed in fulfillment of Josh Weaver’s Ph.D. degree at Clemson University in May 2020.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Donald Garrett, CGCS, and the staff at the Walker Golf Course at Clemson University for their helpful cooperation and insight with this project.

The research says ...

- EarthMax I increased root length in both years of the study.

- All treatments for thatch weight produced results similar to those of the control, but blackstrap molasses performed better than a number of other treatments.

- Blackstrap molasses provided the greatest root weight in both years, but was one of the statistically lowest in root length.

- Over the two-year study, EarthMax reduced thatch thickness by an average of 29%, and blackstrap molasses reduced it by 30% when compared with the control.

Literature cited

- Carrow, R.N., B.J. Johnson and R.E. Burns. 1987. Thatch and quality of Tifway bermudagrass turf in relation to fertility and cultivation. Agronomy Journal 79(3):524-530 (https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj1987.00021962007900030025x).

- Johnson, B.J., R.N. Carrow and R.E. Burns. 1987. Bermudagrass turf response to mowing practices and fertilizer. Agronomy Journal 79(4):677-680 (https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj1987.00021962007900040019x).

- McCarty, L.B. 2018. Golf turf management. CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group, Boca Raton, Fla.

- McCarty, L.B., R.B. Cross and S.C. Green. 2016. Evaluation of Bio-Enzyme and other chemical thatch control products. (https://www.earthfort.com/portfolio-items/clemson-university-study/). Accessed Jan. 27, 2020.

- McCarty, L.B., M.F. Gregg and J.E. Toler. 2007. Thatch and mat management in an established creeping bentgrass golf green. Agronomy Journal 99(6):1530-1537 (https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj2006.0361).

- Schmidt, R.E., E.H. Ervin and X. Zhang. 2003. Questions and answers about biostimulants. Golf Course Management 71(6):91-94.

Josh Weaver was a graduate student at Clemson University and is currently an assistant professor of horticulture at Auburn University, Auburn, Ala. Bert McCarty is a professor of turfgrass science in the Department of Plant and Environmental Sciences at Clemson University, Clemson, S.C.