Figure 1. A native area at Robert Trent Jones Golf Course in Ithaca, Tompkins County, N.Y., was one of the research sites for this project. The plots are being flagged by Martin Ward for vegetation management treatments. Photos by Kyle Wickings

Editor’s note: This research was funded in part by a grant to GCSAA from the Environmental Institute for Golf.

The annual bluegrass weevil (Listronotus maculicollis) remains a major pest of short-mowed turfgrass in the northeastern United States. The difficulties in managing annual bluegrass weevil stem from a number of factors, including their complex biology, cryptic habits and the emergence of pesticide resistance (2).

Many aspects of annual bluegrass weevil biology remain poorly understood. For instance, little is known about how environmental traits in overwintering sites influence winter survival. The weevil overwinters as an adult, primarily in tall or thick vegetation, including leaf litter in forested edges and grassy natural areas.

These areas, especially golf course natural areas, often receive distinct management inputs such as herbicides, leaf litter movement or removal, mowing, selective planting, and even burning. Few studies have examined winter biology of annual bluegrass weevil (1), and, to our knowledge, no studies have assessed the impact of site management practices on the weevil’s winter survival.

The objective of this project was to quantify the impact of different vegetation management practices commonly employed in golf course natural areas on annual bluegrass weevil overwintering. To address the objective, plots were established on two golf courses with known annual bluegrass weevil populations: Robert Trent Jones Golf Course, Ithaca, N.Y., and Onondaga Golf and Country Club, Fayetteville, N.Y.

At both sites, five common vegetation management practices were applied to the plots. We then sampled plots on both golf courses in spring 2017 to assess natural weevil densities. At one site (Ithaca), adult weevils were confined to mesh cages at the soil surface during the winter of 2016-2017 to evaluate overwintering success among the different vegetation management treatments.

Site establishment

The experiment was carried out on golf courses in Tompkins County and Onondaga County, N.Y. In fall 2016, six replicate blocks, each about 20 feet × 20 feet (6 × 6 meters), were established on each course. Each block was divided into five 6.5- × 6.5-foot (2- × 2-meter) plots, each spaced 6.5 feet apart. All blocks were separated by about 10 feet (3 meters). At each site, the entire experimental area was established in a 65.6- × 131-foot (20- × 40-meter) area within a single golf course natural area running adjacent to, and approximately 5 to 10 feet (1.5 to 3 meters) from, mowed rough (Figure 1).

In October through November of 2016, each plot received one of the following five treatments: 1) mowing without removing clippings; 2) mowing and removing clippings; 3) herbicide application; 4) herbicide application, mowing and removal of clippings; or 5) unmanaged control.

Figure 2. A treatment plot at Robert Trent Jones Golf Course after mowing and clipping removal.

Plots were assigned evenly to each replicate block. All mowing within plots was done with a walk-behind mower to minimize equipment traffic between plots. In clipping-removal treatment plots, clippings were collected using an attachable bag on the mower (Figure 2, above). The bag was removed for plots where clippings were retained. Herbicides were applied with a backpack sprayer.

Annual bluegrass weevil field arenas

The initial intent of the project was to monitor naturally overwintering weevil populations, but densities of adult weevils observed in the area of the experiments were low late in the season. Therefore, to ensure that weevils were present so that treatments could be evaluated, weevils were placed in small mesh sleeves (“cages”) at the soil surface within the plots at Robert Trent Jones GC.

The sleeves, which were made of aluminum window mesh, were cylindrical and approximately 6 inches (15 cm) long and ¾ inch (2 cm) in diameter. Soil cores were 4 to 5 inches (10 to 12.7 cm) long and roughly the same diameter as a sleeve.

Figure 3. Weevils were added to a mesh sleeve (top), and then the closed sleeve containing soil and weevils was inserted into the soil.

Each core, along with its dead surface vegetation, was installed in a sleeve. After a soil core was inserted carefully into the sleeve, four adult annual bluegrass weevils were placed on the soil surface within each sleeve (Figure 3, top). Sleeves were crimped at the top, closed with a staple, and then inserted into the original soil core hole and positioned so the weevils were flush with the surrounding soil surface and nested within the surrounding vegetation (Figure 3, bottom). Five sleeves were installed in each of the 30 plots for a total of 150 weevil sleeves (600 weevils).

All weevils used for the study were collected on-site from a nearby rough or were heat-extracted from blue spruce needle litter using Berlese funnels. Weevils were kept alive on moist filter paper until being added to the sleeves.

Soil temperature tracking

To evaluate the impact of the vegetation management practices, we also installed soil temperature loggers (iButtonLink) in a single replicate block at the Robert Trent Jones GC site. iButton loggers were placed in 50 ml plastic tubes on top of a bed of oven-dried clay. The plastic tubes were capped and sealed with parafilm and then inserted into the soil so that the iButton was positioned at the soil surface and embedded directly in the surface vegetation of the plot. Two loggers were installed per plot and, once deployed, were allowed to collect data continually at 2-hour intervals from December 2016 through March 2017.

Spring sampling

All weevil sleeves were harvested at the Robert Trent Jones GC site on April 4, 2017. Each sleeve was carefully removed from the ground and transported to the lab. In the lab, each sleeve was cut open, and soil was sorted to locate each of the four weevils. Weevils were recorded as live, dead or missing.

In addition, at both golf courses, five soil cores — each 2.5 inches (6.35 cm) in diameter × 2.5 inches deep — were harvested from each plot and placed on heat extractors at the New York State Agricultural Experiment Station in Geneva, N.Y., to extract any naturally overwintering annual bluegrass weevil adults.

Results

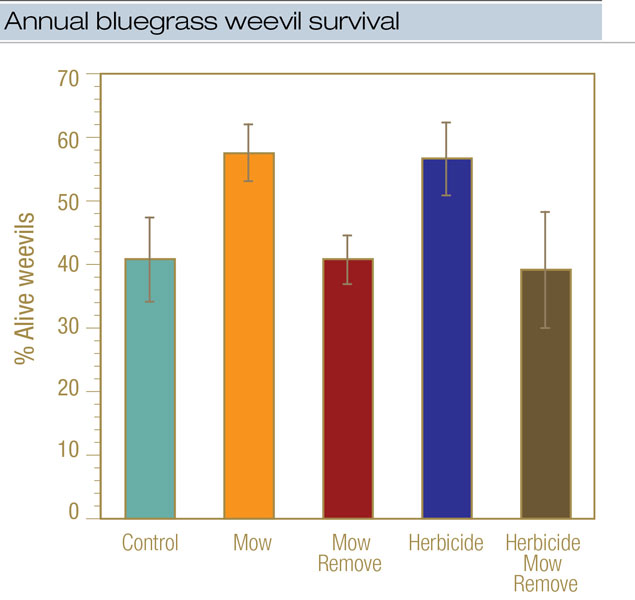

When confined to the mesh sleeves at the soil surface, average annual bluegrass weevil winter survival was approximately 48% and ranged from a low of 40% to a high of 60%. Survival was lowest in untreated control plots, plots where vegetation was removed following mowing alone, or plots that received mowing and vegetation removal plus herbicide application (Figure 4, below).

Figure 4. Annual bluegrass weevil overwintering survival differed under various natural area management treatments in Ithaca, N.Y. (from left): a management-free control; mow and leave clippings; mow and remove clippings; herbicide only; apply herbicide, mow and remove clippings.

In contrast, survival was greatest (~60%) where vegetation was mowed or killed by herbicide but left in the field. Unfortunately, in spring 2017, the recovery of naturally overwintering weevils via heat extraction from soil cores was too low to compare their survival with that of weevils in mesh sleeves.

Soil temperature data suggested that soil microclimate is influenced considerably by vegetation management practices in golf course natural areas. For instance, soil temperature from Jan. 11 to Jan. 24 ranged from a low of approximately 14 F (-10 C) to a high of 68 F (20 C), and we observed less fluctuation in unmanaged control plots or plots receiving only herbicide than in plots where vegetation was mowed; mowed and removed; or treated with herbicide, mowed and removed (Figure 5).

Discussion

The results of this project suggest that management practices employed in golf course natural areas have the potential to influence the success of overwintering for annual bluegrass weevils. Specifically, mowing or treating overwintering areas with herbicide has no impact on annual bluegrass weevil overwintering as long as vegetation is removed from the area. If, however, mowed or herbicide-killed vegetation is not removed, weevils may be better able to survive winter conditions at the soil surface.

The findings suggest that the differences observed in weevil winter mortality may be partly related to variation in soil microclimate conditions induced by vegetation management. For instance, managed habitats with the highest and lowest observed winter survival (herbicide only vs. herbicide-mow-remove) also corresponded with the lowest and highest respective degree of variation in winter soil temperature. The presence of excessive vegetation at the soil surface may create a more buffered winter habitat for overwintering weevils, but this pattern did not hold for all treatments.

Given the persistent and growing challenges of managing annual bluegrass weevil on U.S. golf turf — including pesticide resistance and the limited availability of effective pesticides — it is critical to gain a better understanding of annual bluegrass weevil ecology and how it may be exploited to manage weevil populations. The findings indicate that vegetation management practices employed in annual bluegrass weevil overwintering areas may not have the capacity to enhance control of the weevil. They do, however, reveal that any practices resulting in accumulated dead plant residue in natural areas could lead to more successful annual bluegrass weevil overwintering.

I anticipate continuing work on the winter ecology of annual bluegrass weevil to better characterize the relationships between natural area composition and management practices and their impacts on annual bluegrass weevil winter survival and spring damage incidence.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Rob Pierpoint and David Hicks for their assistance and for allowing access to golf course natural areas, and also to Natalie Bray, Abigail Wentworth and Martin Ward for their contributions to the project.

The research says ...

- This project aimed to quantify the effects of five winter management practices on winter survival of annual bluegrass weevils. Treatments were applied to test plots on natural areas of two golf courses in northeastern New York.

- Weevil survival was lowest in untreated control plots, plots where vegetation was removed after mowing, or plots where an herbicide was applied and vegetation was removed after mowing.

- Weevil survival was greatest when vegetation was left in the study area after it had been mowed or treated with herbicide.

Literature cited

- Diaz, M.D.C., and D.C. Peck. 2007. Overwintering of annual bluegrass weevils, Listronotus maculicollis, in the golf course landscape. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata 125:259-268.

- Kostromytska O.S., S. Wu and A.M. Koppenhöfer. 2018. Cross-resistance patterns to insecticides of several chemical classes among Listronotus maculicollis (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) populations with different levels of resistance to pyrethroids. Journal of Economic Entomology doi:10.1093/jee/tox345

Kyle Wickings is an assistant professor in the Department of Entomology, Cornell University, New York State Agricultural Experiment Station, Ithaca, N.Y.