Short-staffed crews and greater competition for qualified workers are new realities for many in the golf course superintendent profession. Photo by Paul Severn

Editor’s note: GCSAA invited 1,400 members of the Superintendent Research Panel and 600 randomly selected Class A and Class B members to participate in the 2018 Labor Survey. There were 369 responses. The graphs that accompany this article show some of the results of that survey.

Michael Upchurch has no trouble filling out his golf course maintenance crew.

He says maintenance staff turnover is not a problem, that he pays “about market average” for his labor, and, in fact, that retaining staff members has become increasingly easy the past couple of years.

Heck, he even boasts a waiting list for seasonal workers.

“I’ve done this 20 years,” Upchurch says, “and I’ve never had an issue hiring people or keeping people.”

Upchurch, Class A superintendent at nine-hole Henderson (Texas) Country Club and a 20-year association member, is something of a unicorn — a mythical creature rumored to exist but that is rarely, if ever, seen in the wild.

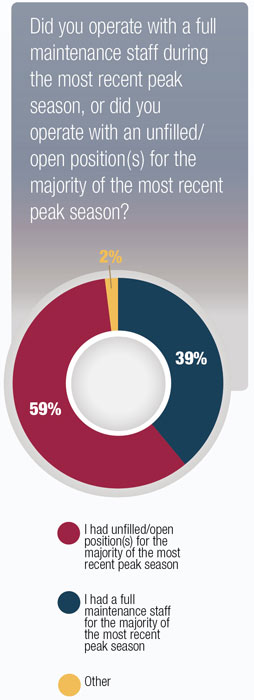

The picture painted by GCSAA members in the association’s 2018 Labor Survey is several degrees gloomier than that illustrated by Upchurch. The majority of survey respondents:

- Either agreed or strongly agreed that staff turnover is a problem.

- Said it was more difficult or much more difficult to retain employees on their maintenance staff over the past two years.

- Described their local labor market in regard to hiring maintenance staff employees as bad or very bad.

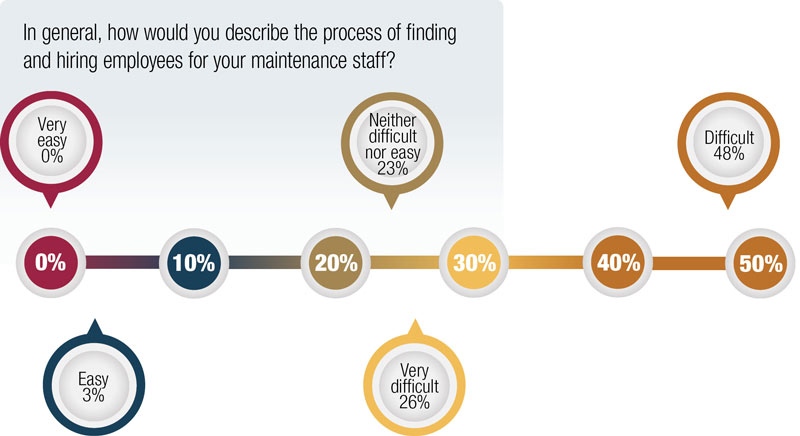

And an overwhelming 74 percent described the process of finding and hiring maintenance staff employees as difficult or very difficult.

Perhaps the most damning statistic, however, is this one: Asked in 2012 to describe the labor market, just 19 percent of respondents described it as bad or very bad; asked again in 2018, a whopping 63 percent used the same qualifiers.

“Oh my gosh,” exclaims sports economist Todd McFall, an assistant teaching professor at Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, N.C. “That’s surprising that it went up that much.”

Blue-collar workers scarce

Don’t misunderstand: McFall knows all about all the issues that have led the golf course maintenance industry to this point. And in that regard, golf courses aren’t alone. Unemployment in 2012 was around 8 percent. Today, it’s around 4 percent, so far fewer people are looking for work.

And then there’s this: According to a December 2018 analysis by The Conference Board, a nonprofit organization that studies the business climate in the United States, blue-collar workers are now scarcer in the U.S. than white-collar workers, reversing a decades-long trend. The group forecasts growing blue-collar labor shortages will continue in 2019 and beyond.

The labor survey results reflect that reality. Asked which maintenance staff positions are most difficult to retain employees for, an overwhelming 74 percent of respondents said crew member/equipment operator. Assistant superintendent was a distant second at 19 percent.

It’s a pain point Kevin Shook knows all too well. Shook, Class A superintendent at Point Rock Golf Club in Elkhart, Kan., is his course’s only full-time employee. Point Rock used to have three full-timers — one in the clubhouse and one assisting Shook on the course. One retired and one moved, and it was decided, Shook says, that they would not be replaced by full-time employees because the nine-hole municipal course couldn’t afford to pay benefits.

So Shook, a 20-year GCSAA member, has to fill his staff with part-time employees drawn from a tiny small-town Kansas employment pool. For insurance reasons, Shook can’t hire anyone under 18, so most high schoolers aren’t an option.

Oh, yeah — and everyone he hires must be a resident of Morton County (population ±3,200), where Point Rock is located.

“I’m short-handed,” Shook says. “There have been times I’ve hired only two people because I’ve only gotten two applications. I would have hired three, but I only got two applications.”

Shook says he has been fortunate to hire a few retirees — “They’re fantastic,” he says. “They do everything you ask them to do. They’re here every day.” — and has hired a few youngsters after they came of age.

“I’m a middle-school basketball coach, so I tell them to remember me when they turn 18,” he says. “I’ve been really blessed. I had some employees I hired when they were 18 and had them four or five years. They enjoyed the work. They moved on, but wish they could make the money they’re making now and work on a golf course.”

Labor crunch felt coast to coast

The situation isn’t unique to small-town middle America.

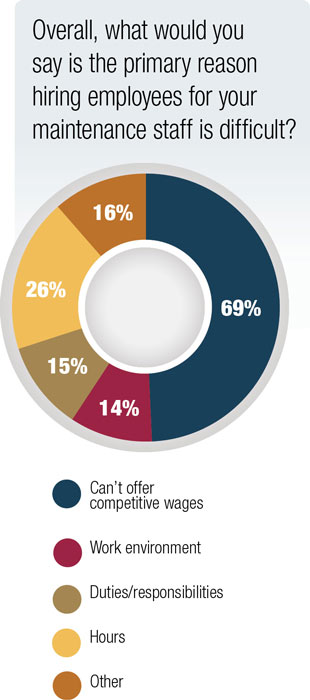

“We’ve been hurting the last two, three years,” says Scott Phelps, CGCS, superintendent at The Golf Club at Newcastle in Newcastle, Wash., just outside Seattle, where the minimum wage is $15 or $16 per hour, depending on company size. “It’s hard to hire people when you know wages are going through the roof. You have to pay more, which means you have fewer people to keep to your labor budget.”

Phelps says he considers the crew at the 36-hole, daily-fee course fully staffed at 38 members. He hit that number for a grand total of one week last summer. He says his staff size has shrunk 25 percent in his 11 years at The Golf Club at Newcastle.

“When I started here, obviously employment was down,” says Phelps, a 28-year GCSAA member. “It was pretty easy for me to pay just over minimum wage and not have a shortage. Nowadays, I put money in the budget. I have the money to hire. I can’t get people to come in and fill out an application.”

It’s not for want of trying. Phelps rattles off his recruiting efforts: Indeed, Craigslist, Facebook, “all the social media,” high schools, job fairs and college career fairs.

“I think we’re beating it to death trying to find workers,” Phelps says. “I think that right there, labor, is our industry’s biggest issue.”

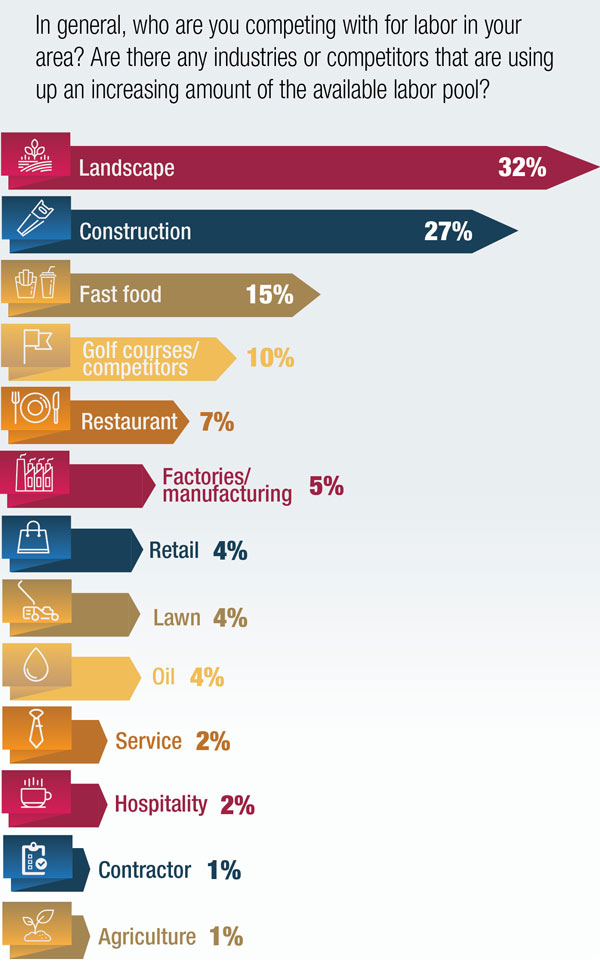

“It’s tough,” echoes Jeff Holliday, CGCS, a 28-year GCSAA member who oversees the 27-hole private Salisbury Country Club in Midlothian, Va., just outside Richmond, Va. “We’re competing with contractors and landscapers paying $2 or $3 more than we are. I’ve been at my club 18 years. When I first got here, the migrant labor force was unbelievable. At least once a week, I’d have a migrant laborer walk up to my door and say, ‘Hey, I need a job.’ Now I have three migrant laborers on staff. I used to have 14.”

Holliday has had to eliminate positions and raise wages to retain employees, who, he says, appreciate the benefits the course provides, which include insurance, uniforms and occasional meals. He uses the Snagajob app to fill shifts and is considering a shift differential to incentivize weekend work.

“The environmental conditions are tough to work in,” Holliday says, “and you have to work weekends. So that’s something we’re looking at. We have to figure out a way.”

A defining moment for the golf industry?

Half a country away, Matt Urban is of the same mind. Urban, Class A superintendent at 18-hole semiprivate Artesia (New Mexico) Country Club and a 15-year association member, echoes many of the familiar refrains from the labor survey: Golf courses can’t afford to match “Walmart cart-pushers making $15 an hour;” millennials aren’t attracted to the industry; turf school enrollment continues to decline (see “Turf enrollment: A slowdown in the downturn?” below).

“I’m moving money away from the golf course,” Urban says, “from things I’d like to do to the golf course. I’m having to sacrifice on that, sacrificing capital dollars into the operations budget to compensate a guy fairly. We’re increasing revenue. We’re fortunate on the country club side we can do that. At public courses, you have to charge more because of green fees, and how many golfers do you lose?

“It’s a difficult balance. It seems to me we’re in a weird limbo in the industry. I think we’ll look back and say we were at a place where we could have done some things to remedy this. I don’t know what those things are. But there are smart people in this industry. As a group, there are a lot of smart people, and I hope they come up with things to remedy this situation we’re in.”

One superintendent’s success

Which brings us back to Upchurch, the lucky guy who says he’s never had a hint of a problem hiring or retaining staff.

What’s his secret?

“I don’t know that I really have a secret,” he says. “I try to hire people who enjoy working outside, and once I get ’em hired, they don’t want to leave. I can’t pay a lot. What I tell the younger guys, even the older guys, ‘To keep a good employee, they’ve got to be happy.’ I tell ’em, ‘If you’re not having fun out there, go find another job, and I’ll stand behind you 100 percent.’

“The big deal is to have fun. You can’t be a slave driver. You’re not a warden at a prison. These people can go out and get other jobs. They’re there because they need a job or they enjoy what they’re doing.”

A mentor told Upchurch to vary his staff members’ responsibilities, so he does that religiously.

Sometimes he gets even less conventional.

“I love having fun,” Upchurch says. “Last Thursday, we loaded up at 1 o’clock, and I had a fishing pole for each one of ’em. We went down to the lake and went fishing all afternoon. That’s what I do.”

Sounds better than one particularly pessimistic survey respondent’s answer. Asked for any tips to pass along to fellow superintendents to help alleviate the labor crunch, their response was, “Prayer!!!!”

Turf enrollment: A slowdown in the downturn?

Just five years ago, it became obvious that one of the main pipelines supplying the golf course superintendent talent pool was drying up. Rapidly.

A 2014 GCSAA survey of U.S. turf schools showed a marked downward trend in turf program enrollment.

According to the results of the GCSAA’s 2018 Turf School Survey, that trend, at the very least, might be slowing.

Back in 2014, in response to the question, “How have enrollment numbers in your turf program changed over the past 10 years?” 70 percent of respondents reported lower numbers than in 2004, while just 10 percent noted an increase.

Five years later, both numbers have changed drastically. Though 54 percent of respondents reported lower numbers for the five-year period ending in 2018, 23 percent — more than double than in 2014 — reported higher numbers. The remaining 23 percent reported enrollment was “about the same,” a slight uptick from 20 percent over the previous 10 years.

Broken down further, some of the increases are significant, perhaps significant enough to offset some declines. For instance, only 15 percent of respondents with declining enrollment reported declines of 65 percent or more: 10 percent reported declines of 75 percent, while 5 percent reported a 65 percent decrease.

However, among those who reported enrollment increases, 33 percent reported increases of 65 percent or more. Those increases were split evenly: 11 percent each for increases of 65 percent, 100 percent, and more than 100 percent.

Golf course management is the “most attractive” area of interest among respondents’ incoming students (85 percent) — well ahead of sports turf management (64 percent), landscape design/maintenance (31 percent), turfgrass research (15 percent) and “other” (15 percent).

Also notable is the fact that participation in online courses has increased in the past five years. Although less than half of respondents (38 percent) reported that their turf programs offer online courses, programs that do offer online coursework saw a significant (47 percent) or slight (13 percent) increase in participation.

Of the respondents, 85 percent offered a bachelor’s degree in their turf programs, 36 percent offered an associate degree, and 18 percent offered a certificate.

The survey was sent to 68 turf school administrators from a list provided by the Department of Education. There were 40 responses.

Andrew Hartsock is GCM’s managing editor.