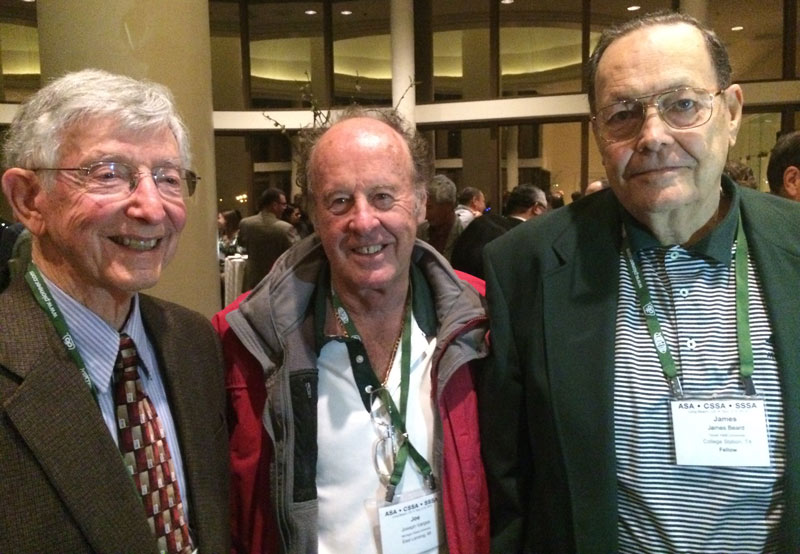

James B. Beard, Ph.D. (right), with Paul Rieke, Ph.D. (far left) and Joe Vargas, Ph.D. Photo courtesy of Kevin Frank

The students of James B. Beard, Ph.D., had a name for him.

“We used to call him ‘the pope of turfgrass,’” says Johnny Walker, GCSAA South Central field staff representative. “His mind was always working on the next research project and was so interested in what made the plant work.”

Beard, 82, passed away Monday evening. He is considered a pioneer in turfgrass science, and spent much of his career at universities, including Michigan State and Texas A&M, which is where Walker studied under him.

A native of Bradford, Ohio, Beard authored numerous works, including the famed “Turfgrass: Science and Culture” in 1973, “Turf Management for Golf Courses,” and 2004’s “Beard’s Turfgrass Encyclopedia for Golf Courses, Grounds, Lawns, Sports Fields.” Beard, who wrote hundreds of peer-reviewed papers and technical papers, donated his collection of turfgrass research materials in 2003 to the Turfgrass Information Center at Michigan State, where he taught from 1961 to 1975.

“He is the grandfather — the godfather — of turfgrass science. I don’t think anybody would argue with that,” says Kevin Frank, Ph.D., associate professor at Michigan State. “What stands out was his leadership in making turfgrass a science.”

The recipient of GCSAA’s Distinguished Service Award in 1993, Beard earned his bachelor’s degree in agronomy from Ohio State University and, later, both his master’s in crop ecology and doctorate in turfgrass physiology from Purdue University. He founded the International Sports Turf Institute, headquartered in College Station, Texas, and had been professor emeritus of turfgrass at Texas A&M since 1993.

“He was focused, congenial, respectful. He was a visionary when it came to building a strong research program across the board,” says Paul Rieke, Ph.D., an authority on turfgrass soil and nutrition in his own right and a colleague of Beard’s at Michigan State. “He was a very precise scientist. He clearly challenged the status quo.”

Joe Vargas, Ph.D., was a colleague and longtime friend of Beard. Vargas launched his career 50 years ago as a researcher at Michigan State. “I started Nov. 1, 1968, and by the second week, he dragged me up to Boyne Highlands (in Harbor Springs, Mich.) to put out a snow mold plot,” Vargas says. “Before him, we were spray-and-pray guys. Dr. Beard was the first real scientist to understand why things were happening, such as why there is stress in the plant. He did the research. The main thing he taught me was how to be a critical researcher and not just jump into something. I would go talk to somebody, which usually was him.”

Never far away was Harriet Beard, who was a wife and a teammate. So much, in fact, that she collaborated with him and their son James on the book “Turfgrass History and Literature: Lawns, Sports, and Golf,” which was selected as the 2015 recipient of the American Library Association’s Oberly Award for best bibliography in agricultural or natural sciences. Often, Beard would supply handwritten work, and Harriet, who grew up on a farm that adjoined the Beard family’s, would type it up.

Beard’s impact is felt still.

“I met him when I had just started here (in 2010),” says Ben Wherley, Ph.D., associate professor at Texas A&M. “I visited with him and Harriet at their house. For someone who was supposed to be retired (Beard taught at Texas A&M from 1975 to 1992), he was still very active, and you could see the two of them were very close. You still could see the enthusiasm for turfgrass science. It was his life. We still cite a lot of his workings and teachings.”

Howard Richman is GCM’s associate editor.