From left: Billy Powell, Marcella Powell, Larry Powell, Bill Powell and Renee Powell, circa 1960. Photo courtesy of the Powell family

Forty-seven years ago, a flood wiped out 12 bridges at Clearview Golf Club. There was zero chance, however, that it would totally wash away what happened there 70 years ago. A devoted family — courageous and fearless — ensured its longevity.

After serving his country in World War II, Bill Powell returned to the United States, hoping the racial climate had changed. Simply by wanting to play golf, he learned it hadn’t. African-Americans such as Powell encountered a country still far from colorblind.

Powell faced discrimination in many ways. He was prohibited from playing on a golf course because of his color. Rejected for a GI loan meant to help service members buy a home, Powell turned to his brother, Berry, who took out a second home mortgage, and two African-American doctors to assist in financing his golf dream.

Powell and his wife, Marcella, searched for a piece of land in 1946. When they found a dilapidated dairy farm that suited their eye near the tiny village of East Canton, Ohio, something massive emerged.

Using his bare hands to do much of the grueling, endless and seemingly impossible tasks, Powell opened Clearview Golf Club with nine holes in 1948. Fondly dubbed “America’s Course” because Powell wanted a place where anyone could play, Clearview was the first and remains the only golf course to be designed, constructed and owned by an African-American.

Although Powell was victimized by racism, he never played the race card. “Dad said the only card here is the scorecard,” says Powell’s son, Larry, a 44-year GCSAA member and Clearview’s superintendent since 1971. Larry’s sister, Renee Powell, is the club’s PGA professional.

Bill Powell — an agent of change — was a 37-year GCSAA member when he died at 93 in 2009. His acts of bravery and a determination to overcome racial injustice helped shape his legacy, and a slew of people through many decades have kept the dream alive.

“I can’t emphasize enough that this course would not be here without the help of so many people,” Larry says. “At a small operation like this, it was critical for the survival of Clearview. It took a family.”

What the Powells achieved at Clearview has been applauded and recognized on many occasions. The latest distinction comes in the form of GCSAA’s highest honor, the 2019 Old Tom Morris Award, which has been presented annually since 1983 to an individual — and now a family — who, through a continuing lifetime commitment to the game of golf, has helped to mold the welfare of the game in the manner and style exemplified by Old Tom Morris. They’ll officially receive the award Feb. 6 at the Golf Industry Show in San Diego during that event’s Opening Session, which is presented in partnership with Syngenta.

A football legend who was at the center of one of the most famous plays in the sport’s history understands the importance of how far Bill Powell’s imagination and grit took him.

“He had that determination, that drive, all for the love of the game. I mean, he just took it to a new level of appreciation,” says Franco Harris, the iconic running back for the Pittsburgh Steelers, who was on the receiving end of the “Immaculate Reception” in a 1972 AFC divisional playoff game — as well as golf lessons from Bill Powell. “When I was introduced to Mr. Powell, really, it was meeting history.”

A dream is born

Bill Powell was no stranger to the racial divide that held sway in the country during the early part of the 20th century. From the doorstep of his home on Pennsylvania Avenue in Minerva, Ohio, where he was raised, he could see a patch of land where the Ku Klux Klan burned crosses.

But the son of a Bible-reading father and the grandson of Alabama slaves also grew up near what would become his future passion. Powell was just 9 when he learned that Edgewater Golf Club was being built just 7 miles from his home. “Dad told me he would light up when he saw that course,” Larry says.

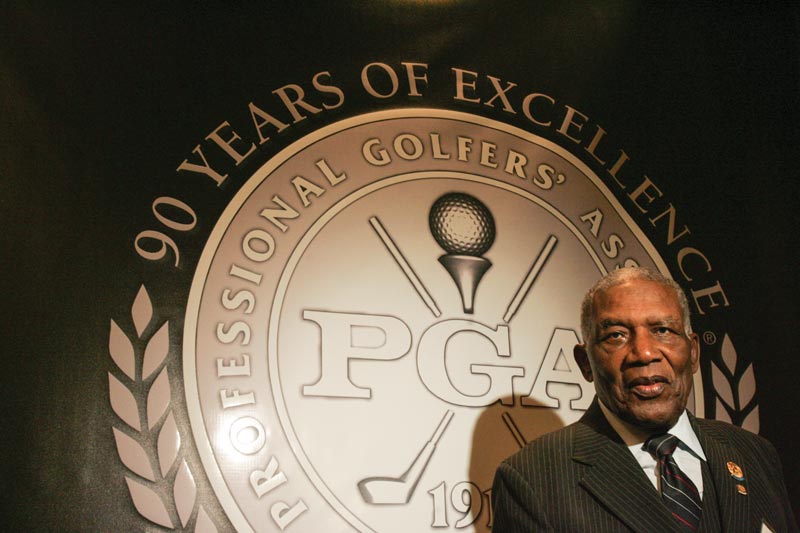

Bill Powell was presented with the PGA of America’s Distinguished Service Award in 2009. He passed away later that year. Photo courtesy of the Powell family

Bill Powell became a caddie when Edgewater opened. Not just an ordinary caddie, either. “He and Berry carried two bags at once to make more money (35 cents per bag),” Larry says. “The caddie master noticed them, and so they also began to work for the maintenance crew. The club saw how aggressive and hungry those boys were to work, and they cleaned up fast. Dad fell in love with the sport. All aspects of it.”

Bill Powell was quite an athlete. He was the only African-American on his high school football team. And, as a 5-foot-9, 200-pound sturdy force, was its captain. The squad was undefeated in 1932 and outscored its opponents 332-0. “Anything short of perfect was always unacceptable to him,” Larry says.

This is how fondly one of Bill Powell’s classmates thought of him: Ralph Petros, who was valedictorian, skipped graduation when he learned that Powell would have to walk into the ceremony by himself instead of being paired with someone like everyone else was (the school was 99 percent white).

At Wilberforce (Ohio) University, Bill Powell played golf, including in the first interracial match between colleges when historically black Wilberforce faced Ohio Northern, a white college, in 1937 (Wilberforce won).

Drafted into World War II, Powell was a sergeant who oversaw 1,200 truck units that were deployed in England in preparation for the upcoming D-Day invasion. When he came home following the war, Powell soon realized it was all too uncomfortably familiar. Stationed in the South before returning to Ohio, he witnessed German prisoners of war being treated better than American soldiers of color. The POWs were issued new outfits to wear. Powell was given salvaged clothing.

He went back to the job he held before the war, working as a security guard at Timken, a bearing and steel company. Meanwhile, Powell’s resolve to build a golf course where everyone was welcome never diminished. He worked nights at Timken as he built Clearview, which included a four-bedroom farmhouse that required him to install plumbing. The job it took to shape the course was monumental.

“He physically manhandled it when he cleared the land,” says Larry, noting that a World War II-era Jeep was used to pull a five-gang mower on the ground his father had planted with a hand seeder tied around his neck. Even today, Clearview has no modern irrigation system. A Massey-Ferguson tractor connected to a generator pumps water from a well to a pond for supplemental purposes. The main water force comes from a power takeoff pump that sends water directly to the course. “We only irrigate greens and tees,” Larry says. “There’s no fairway irrigation. Just rain.”

A second nine holes opened in 1978, and today, Clearview is an 18-hole, par-72, 6,600-plus-yard layout with 22 bunkers. It has Colonial bentgrass/fescue/rye fairways, a fescue/rye/bluegrass mix in its roughs, and greens averaging 7,500-square feet, composed mostly of L-93 creeping bentgrass with a couple of Penn G-6 greens.

The brother-and-sister act of Renee and Larry Powell keeps Clearview Golf Club in East Canton, Ohio, humming. Renee, a former LPGA player, is the club’s PGA Club Professional. Larry, a 44-year GCSAA member, has been the superintendent since 1971. Photo by Craig James

It’s a work of art to Clearview historian Jeff Brown, who spearheaded the drive to secure the facility as a National Historic Site in 2001. Brown, as do countless others, refers to Powell

as “Mr. P.” “He didn’t have hate or display anger and bitterness. But there was a deep hurt there,” Brown says about the racial obstacles Powell endured. “He said, ‘The only color that matters to me is the color of the greens.’ He still inspires people after he’s gone.”

And Powell’s family is an ideal match for this award. “The Powells stand for what Old Tom Morris embodied,” says GCSAA CEO Rhett Evans, noting that Morris was a four-time British Open champion and Scottish greenkeeper for four decades at the Old Course at St. Andrews. “They built the golf course, operate it, maintain it, play the game and work every day to help others enjoy it.”

After reading a blurb about Powell in Reader’s Digest, golf course architect Mike Hurdzan, Ph.D., was inspired to write a letter to him, telling Powell he appreciated his contributions. Later, Hurdzan was in the region and paid a visit to Clearview. “He treated me like a son,” says Hurdzan, the Old Tom Morris Award recipient in 2013 whose company constructed the master plan for restorations at Clearview several years ago. “Everyone recognizes what the Powells have done for the game of golf. Everything they have, they gave to the game. They don’t have a mercenary bone in their bodies.”

Bill Powell’s twin sisters, Mary Walker and Rose Mathews, are still alive and in their 90s. Mathews mows her own lawn. She also still lives in that house on Pennsylvania Avenue. She marvels at her brother’s accomplishments. “I don’t know how he did it. He was just determined. That’s all I can say,” Mathews says.

Family matters

When Norm Hill looks at Larry Powell, it is almost like seeing double.

“Larry is very much like his dad. Self-made. Dedicated to what he’s doing. The degree of pride he takes in Clearview — it isn’t superficial. It’s very deep. Larry knows every inch of ground there,” says Hill, a Powell family cousin who laughs after saying that family vacations as a youth meant driving 30 minutes from Akron, Ohio, to Clearview to mow grass and pick up rocks. “If you’re looking at that course, you’re looking at Larry. If you’re looking at Larry, you’re looking at Bill.”

Undoubtedly, Bill Powell was a role model for Larry, 66, who is devoutly committed to continuing what his father started. “I was born into it. At 8, I learned how to mow a green. They were getting me in shape,” Larry says. “Dad got upset when someone said the word ‘can’t.’ It was one of his driving forces. The whole family put blood, sweat and tears into this. Our parents taught us to fight for what you believe.”

Two of those family members are no longer here. Larry’s older brother, Billy, was 26 when he was murdered more than 40 years ago in California, yet his efforts at Clearview remain visible. “He worked side by side dad as a youngster,” Larry says. “I played football in seventh grade. Billy said he’d take care of the course while I was in school. If it wasn’t for him, this course wouldn’t be here. Take any of these people away, and this course wouldn’t be here.”

Marcella, perhaps the unsung star, passed away in 1996. Not only did she run the golf shop, she also oversaw club finances, was a Girl Scout leader and launched a women’s league in the 1950s. “When I was little, she made my clothes,” says daughter Renee, one of Bill and Marcella’s three children born at the hospital where Marcella had been refused admittance when she attempted to enroll in nursing school.

Larry, meanwhile, logs enormous hours. Not as many as he used to, however, when he had a second job with the U.S. Postal Service. “One time I was up 80 hours straight,” says Larry, who has taken a pass on back surgery but did have replacement surgeries on both knees. “You learn to just keep pushing through. Since we’re a small operation, it’s a lot of work (Larry has a staff of two, sometimes three, helping him). You’re never done.”

His fiancée, assistant superintendent/horticulturist Teresa Cole, has been at Clearview since 1988. She mows greens, is a master with flowers, was instrumental in converting the greens to their current cultivars, and was involved in the clearing of the land and the grow-in for improvements done in 2002, which included bunkers, tees, greens and fairways. “She’s a member of the Powell family,” Larry says.

Teresa Cole, assistant superintendent and horticulturist, has been at Clearview Golf Club since 1988. She is also Larry’s fiancée. Photo by Craig James

Assistant superintendent Michael Duffie, who completed his 10th summer on Larry’s staff in 2018, feels fortunate to be part of something special. “I consider it a real honor to work at a course that is famous all over the world,” Duffie says. “I told Renee she’s lucky. Her parents’ breath is still in this building. I don’t have any place like that.”

Renee says Larry has breathed life into Clearview. “No way my dad would’ve been able to keep this golf course without Larry,” she says.

Larry, though, shares the credit. He mentioned Renee, who mowed greens, even at times between events when she was playing on the LPGA, and who excels at teaching golf to an array of people, from children to seniors and those with mental and physical handicaps. “This isn’t just Larry,” he says. “It’s Renee. Teresa. Mom. Brother. Dad. And many others. It’s like a chain. If any of these links were not present, Clearview would not be here today.”

A haven for all

Golfer Judy Sallerson served her country in Operation Iraqi Freedom. Nowadays, you often see her at Clearview, thanks in no small part to Renee Powell.

“I was at Walter Reed (National Military Medical Center) two years, came back to Ohio, never left my house,” Sallerson says. She was enticed to depart the comfort and safety of her home after hearing about what was occurring at Clearview. Renee Powell had initiated Clearview H.O.P.E. (Helping Our Patriots Everywhere). The free program is designed for female veterans to receive lessons and play golf. “When I came here and met people like me who had similar experiences, I came out and never left,” Sallerson says.

Sallerson is among those who’ve gained a mentor and leader in Renee, who was the second African-American (Althea Gibson was first) to play on the LPGA. In September, Renee was recognized by the University of St. Andrews in Scotland for inspiration in diversity in golf and the advancement of women’s social causes. In fact, the university dedicated Renee Powell Hall — the first residence hall named for an American. She also was among the first handful of women to be granted membership in the Royal & Ancient Golf Club of St. Andrews, which ended 260 years of male exclusivity.

“We were like sisters,” says Sandra Post, an LPGA Rookie of the Year who often roomed with Powell while they were on the road. “Bill even said we look alike (Post is white). I said, ‘Bill, what part of this don’t you get?’ Everything people say about Renee is right. She’s wonderful. She was destined to do something great.”

Renee Powell teaches the game to all comers. She has the credentials — Powell played on the LPGA for more than a decade, beginning in 1967. Photo by Craig James

All you need to know about how much PGA of America President Suzy Whaley treasures Renee is that Powell delivered the nomination speech for Whaley when Whaley was running for vice president. “She’s a role model for me. She’s optimistic about the PGA’s future, always looking forward and not backward, and just wants more people to play the game. That’s what we all want,” Whaley says.

Bina McVehil, a female Vietnam veteran who Renee says smiled much more than she did upon her first visit to the golf course, simply is thankful for what Clearview has done for her. “I needed this. I feel I belong somewhere,” McVehil says.

The Old Tom Morris Award is a testament to what her family accomplished, Renee says. “Superintendents are the salt of the industry. It’s working the ground, the thing that daddy and Larry had to do,” she says. “Dad didn’t go by the book. He did it himself. He was about the earth, and that’s what this award is about. We all live to play on courses. You can’t play in the parking lot. You need someone to take care of the golf course. Old Tom Morris was the first one.”

Lasting legacy

Someone has to call Bill Powell a pioneer. Fred Tattersall happily obliges.

When The First Tee was in need of a summer life skills academy to teach youths core values and how to play better golf, Tattersall suggested 20 years ago to The First Tee’s then-executive director, Tod Leiweke, that they name a scholarship for the program in honor of someone.

“I said it makes sense to name it for somebody that’s really been a pioneer in the golf industry. I watched a film of her (Renee, who helped launch The First Tee) and her father and was blown away by his service to the country, how he loved golf so much that he got together with people to build Clearview, and did that after work,” says Tattersall, senior adviser for 1607 Capital Partners in Richmond, Va. Tattersall and his wife, Roddy, gave generously to The First Tee, which also established the William J. Powell Scholarship, allowing youngsters to attend The First Tee Life Skills and Leadership Academy.

On occasion, the Tattersalls would fly Bill and Renee to The First Tee events around the country. “We’d take them so they (First Tee participants) could see someone who overcame what he did. One of the nine core values is perseverance. What he went through is perseverance,” Tattersall says. “You knew you were in the presence of somebody who had a big heart, and he had one of the warmest smiles I’d ever seen. Clearview was never a home run financially. I just think it was the passion of doing something he loved. This is a guy who never gave up.”

Sadly, Bill Powell was not formally recognized with honors until late in his life. In 1996, he was inducted into the National Black Golf Hall of Fame (Larry and Renee have since been inducted). In 1999, he was granted Life Member status retroactively by the PGA of America, an organization that had a “Caucasian-only clause” that prevented non-whites from membership until the clause was removed in 1961.

Larry Powell chats with longtime crew member Michael Duffie. Fifty-six years after mowing his first green, Larry is still going strong. Photo by Craig James

In his final year, Powell was the recipient of that organization’s Distinguished Service Award and was inducted into the Northern Ohio PGA Hall of Fame. In 2013, Powell was posthumously inducted into the PGA Golf Professional Hall of Fame.

And where did Powell get the name Clearview? One of the highest points on the course, on a hill near the 16th green, gave him a clear view of the course. The odds were stacked high against him in making that vision of his beloved course possible. Powell accepted the challenge — and all challenges. The indignities. Racial slurs. Course vandals. None of it halted his quest. His piece of work is protected through the Clearview Legacy Foundation, a 501(c)(3) tax-exempt charitable foundation established 17 years ago to preserve Clearview’s legacy and facilities for future generations.

A patriotic soul, Bill Powell had an honor guard hoist a new American flag each year at Clearview. It’s still a tradition there. Obviously, his presence reigns. Hill, the family cousin, is convinced it is worthwhile to sense the Powell family’s spirit in person. “The message I’d give the world: Put Clearview on your bucket list,” he says, “to see what the mind and the heart can do when you are dedicated to something.”

Howard Richman is GCM’s associate editor.