Figure 1. A golf course putting green composed primarily of fine fescues is backed by fine fescue natural rough at Ballyneal Golf Club in Holyoke, Colo., in 2009. Photo by Leah Brilman

As a golf course superintendent managing fescue on your course, you probably know which species you’re managing, especially when it comes to tall fescue (Festuca arundinacea, syn. Schedonorus arundinaceus, syn. Lolium arundinaceum) versus fine fescues (Festuca species). However, how confident are you in recognizing the differences among the fine fescue turfgrasses found in a variety of golf course management situations (Figures 1, 2 and 3)?

Recently, a team of researchers working on a grant titled “Increasing Low-Input Turfgrass Adoption through Breeding, Innovation, and Public Education” from USDA-NIFA through the Specialty Crop Research Initiative has put together an exhaustive scientific review of the fine fescue turf species. This review clearly documents differences in growth, production, establishment, management, utilization, pest tolerance and stress tolerance of the fine fescue taxa (taxa, plural of taxon, which is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms used in the science of biological classification, or taxonomy) (6).

These five fine fescue grasses commonly used in turfgrass systems include strong creeping red fescue (Festuca rubra subspecies rubra), slender creeping red fescue (Festuca rubra subspecies littoralis), Chewings fescue (Festuca rubra subspecies commutata), sheep fescue (Festuca ovina) and hard fescue (Festuca brevipila) (Table 1). They are adapted for use in a variety of areas on the golf course in cool-season climate zones of North America and Europe. These grasses are generally regarded as low-input turfgrass options because of slow growth (less mowing) along with low nitrogen fertilizer, irrigation and pesticide requirements.

There is a lot of confusion and debate regarding the scientific (taxonomic) classification of fine fescues. Therefore, in our review (6), we present the recommended taxonomic classification (see Table 1, Recommended taxonomic classification and characteristics for fine fescues). Our goal is to bring greater clarity and accuracy to the use of scientific names, and to improve overall knowledge of the differences among fine fescue taxa. A greater understanding of these fine fescues may help facilitate better turfgrass management practices by capitalizing on the strengths of individual fine fescue taxa.

Figure 2. Sand Valley Golf Resort in Nekoosa, Wis. The natural rough area in the foreground is fine fescue, and the golf course fairways consist of 30% slender creeping red fescue + 30% Chewings fescue + 20% strong creeping red fescue + hard fescue surrounded by waste bunker areas. Photo by Leah Brilman

Until now, researchers and turf practitioners have frequently referred to these five turfgrasses as a single group (“fine fescues”), which can lead golf course superintendents, homeowners and other turf practitioners to infer that individual taxa — strong creeping red fescue, slender creeping red fescue, Chewings fescue, sheep fescue and hard fescue — all perform similarly, which is not the case. The lack of information and the confusion around the common and scientific naming of fine fescues and the misidentification of fine fescues as a single group often lead practitioners to infer that the individual fine fescue taxa all grow and respond to management and environmental stresses in a similar manner, which is misleading and a significant barrier to transitioning to these low-input turfgrasses (1). Therefore, we are recommending turf practitioners and researchers of these grasses begin to refer to each fine fescue individually, by its specific common or scientific name — recommended herein — in future use.

A brief history of fine fescues

Fine fescues have also been called fine-leaf, fine-leaved or bristle-bladed fescues. These grasses have been used in the turf industry since the 16th century (4, 12). Central Europe is reported to be the center of origin for the Festuca species (10), but fine fescues are native to both Eurasia and North America and were introduced and naturalized in many diverse temperate regions of the world, including the Arctic and temperate zones of Asia, Europe and North America (4).

Fine fescues have been used for golf, lawn and sports (lawn bowls, cricket, croquet, other) turf surfaces in Europe since the 1700s, and possibly earlier (4). Their use in the U.S. gained momentum in the mid- to late 1800s, with creeping red fescue commonly used in lawns, especially in shaded sites in the late 1890s (2, 15, 17). Unfortunately, a majority of research and literature prior to 1970 identifies creeping red fescue or red fescue (F. rubra) but does not specify the subspecies of either strong or slender creeping red fescue. Therefore, it is difficult to know which taxon was studied unless a cultivar or more information is specified (6).

In the 19th century, creeping red fescue was used in polystands with creeping bentgrass (Agrostis stolonifera) on putting and bowling greens in Europe (12, 16). All three F. rubra subspecies — strong creeping red fescue, slender creeping red fescue and Chewings fescue — either when sowed alone or as a polystand with bentgrass, have consistently been an integral part of greenkeeping and fine sports turf in Europe since the 1800s (13). By 1917, creeping red fescue was one of the most desirable grasses, other than creeping bentgrass, for northern U.S. putting greens (17).

Figure 3. Fine fescue golf course fairways can be seen through the fine fescue seedheads in the natural rough area at Sand Valley Golf Resort in Nekoosa, Wis. Photo by Leah Brilman

In the late 1800s, sheep fescue was, at times, recommended over Kentucky bluegrass for lawns with full sunlight and light, dry soil conditions in the northern U.S. (2). However, researchers (7) later argued against the use of hard fescue and sheep fescue in lawns, but mentioned they did make excellent roughs on golf courses. The use of sheep and/or hard fescue in Europe and the U.S. in the late 1800s and early 1900s was often hindered by uncertain and limited commercial seed supplies (12). Researchers (12) remarked at the time that hard fescue showed value in the turf industry, but only as a “second-class turf,” and it could be used along with other fescues or bentgrasses to provide golf course fairways and teeing grounds, but not putting greens.

Chewings fescue is named after George Chewings (1855-1925), who first cultivated, harvested and sold “Chewings fescue” in New Zealand in the 1880s (14, 18). In literature, the common name is sometimes misspelled with an apostrophe (Chewing’s or chewing’s). A challenge in the distribution of this grass was that its germination capacity severely declined because of poor storage and shipping conditions by boat from New Zealand to Europe and North America in the 1930s. This led to greenkeepers becoming apprehensive about using it for golf turf (13). However, this problem was fixed with further seed germination research that led to the development and an understanding of the importance of sealed containers during shipping to maintain low humidity (4, 11).

Breeding and release of improved fine fescue cultivars traces to the 1930s (see Table 2, History of fine fescue cultivar breeding before 1970). Prior to the 1930s, the majority of fine fescues available were common types simply labeled by species name “Chewings” or “common creeping red.” Following the release of these first cultivars, the years after 1960 brought substantial efforts to develop and release improved cultivars. Today, breeding objectives include improved turf quality characteristics, greater seed production and yield, improved resistance to abiotic and biotic stresses, enhanced wear tolerance, ability to persist under low-input management scenarios (5), and improved sod-forming characteristics, including establishment vigor (18).

Scientific research on lawn polystands of fine fescues with other species began to commonly occur in the 1940s and 1950s (6). In the 1960s and 1970s, the three F. rubra subspecies were still more commonly used in turf areas, especially under shade, than sheep fescue or hard fescue, which began to be more commonly used for low-maintenance areas, such as roadsides and golf course roughs (3, 9).

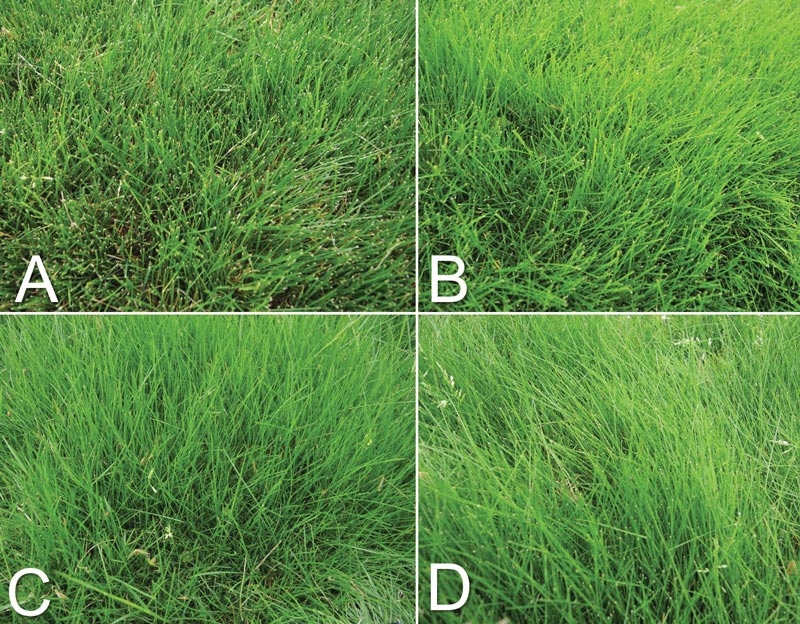

Figure 4. These photographs were taken under the same light intensity to capture genetic color differences among the fine fescues: (A) strong creeping red fescue, (B) slender creeping red fescue, (C) Chewings fescue and (D) hard fescue. Photos by Ross Braun

Today, all five fine fescue taxa are used on a variety of turf areas throughout the mild and northern climates in North America and Europe, more specifically the United Kingdom, Scandinavia, and the Northeast, Pacific Northwest and North-Central areas of the U.S. This includes but is not limited to sites where regulations or reductions in inputs are a major concern, home lawns and parks, shaded areas, infertile or poor conditions, low-maintenance areas (roadsides, native “natural” areas that are “no-mow” or “minimal-mow”), golf course turf (putting greens, fairways and roughs), and sports turf (tennis courts and cricket pitches).

Forthcoming issues

Growth habit and genetic color characteristics are slightly different among the fine fescues (Table 1, Figure 4). All five grasses have very fine leaf texture (narrow leaf width), which can help them be easily distinguished from other turfgrass species but is problematic when trying to identifying one fine fescue taxa from another.

These fine fescues can be distinguished from one another — although it’s a difficult task — by their morphology and other methods. See our article in Crop Science (6) for more information. Regardless of the difficulty of differentiating among these turfgrasses, recognizing the differences in growth, performance, production, establishment, management, pest tolerance and stress tolerance of fine fescue taxa will help golf course superintendents understand the weaknesses and strengths of each fine fescue, which will enhance sustainability. We will present more on these unique differences in future issues of GCM in 2020.

Funding

The authors wish to acknowledge the funding support by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Specialty Crop Research Initiative, under award number 2017-51181-27222. The full manuscript on this literature review of fine fescues is available in Crop Science (https://doi.org/10.1002/csc2.20122).

The research says ...

- This article is the first of four that will document differences in growth, production, establishment, management, utilization, pest tolerance and stress tolerance among the fine fescue taxa.

- Fine fescues, which are native to both Eurasia and North America, have been used for turf since the 16th century and for golf, lawns and sports surfaces in Europe since the 1700s.

- Breeding to improve fine fescue cultivars traces to the 1930s. Today’s breeding objectives include persistence under low inputs; greater seed yield; and improved turf quality, stress resistance, wear tolerance and sod-forming characteristics.

- All five fine fescue taxa are now used on a variety of turf areas throughout the United Kingdom, Scandinavia, and the Northeast, Pacific Northwest and North-Central areas of the United States.

Literature cited

- Barnes, M.R., K.C. Nelson, A.R. Kowalewski, A.J. Patton and E. Watkins. 2020. Public land manager discourses on barriers and opportunities for a transition to low-input turfgrass in urban areas. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening (in press).

- Beal, W.J. 1898. Lawn-grass mixtures as purchased in the market, compared with a few of the best. Proceedings of the Society for the Promotion of Agricultural Science 1898:59-63.

- Beard, J.B. 1973. Turfgrass: Science and culture. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.

- Beard, J.B., H.J. Beard and J.C. Beard. 2014. Turfgrass history and literature: lawns, sports and golf. Michigan State University Press, East Lansing.

- Bonos, S.A., and D.R. Huff. 2013. Cool-season grasses: biology and breeding. Pages 591-660. In: J.C. Stier, B.P. Horgan and S.A. Bonos, editors. Turfgrass: Biology, use, and management. Agronomy Monograph 56. ASA, CSSA, SSSA, Madison, Wis. doi:10.2134/agronmonogr56.c17

- Braun, R.C., A.J. Patton, E. Watkins, P. Koch, N.P. Anderson, S.A. Bonos and L.A. Brilman. 2020. Fine fescues: A review of the species, their improvement, production, establishment, and management. Crop Science (in press). doi:10.1002/csc2.20122

- Dickinson, L.S. 1930. The lawn: The culture of turf in park, golfing and home areas. Orange Judd Publishing, New York.

- Hanson, A.A. 1965. Grass varieties in the United States. USDA Agricultural Handbook 170:1-102.

- Hanson, A.A., F.V. Juska and G.W. Burton. 1969. Species and varieties. Pages 370-409. In: A.A. Hanson and F.V. Juska, editors. Turfgrass science. Agronomy Monograph 14. ASA, Madison, Wis.

- Inda, L.A., J.G. Segarra-Moragues, J. Müller, P.M. Peterson and P. Catalán. 2008. Dated historical biogeography of the temperate Loliinae (Poaceae, Pooideae) grasses in the northern and southern hemispheres. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 46:932-957.

- Kearns, V., and E.H. Toole. 1939. Relation of temperature and moisture content to longevity of Chewings fescue seed. United States Department of Agriculture Technical Bulletin No. 670.

- Lewis, I.G. 1933a. A greenkeeper’s guide to the grasses. 2. The genus Festuca. Journal of the Board of Greenkeeping Research (Spring) 3(8):39-43.

- Lewis, I.G. 1933b. A greenkeeper’s guide to the grasses. 2. The genus Festuca (concluded). Journal of the Board of Greenkeeping Research (Autumn) 3(9):94-98.

- Morgan, A. 1998. The Chewings story. TurfNews 22(6):33-35.

- Piper, C.V. 1921. The first turf garden in America. Bulletin of the Green Section of the U.S. Golf Association 1(2):22-23.

- Piper, C.V. 1924. Golf turf in Britain. Bulletin of the Green Section of the U.S. Golf Association 4(9):219-221.

- Piper, C.V., and R.A. Oakley. 1917. Turf for golf courses. Macmillan, New York.

- Ruemmele, B.A., J.K. Wipff, L. Brilman and K.W. Hignight. 2003. Fine-leaved fescue species. Pages 129-174. In: M.D. Casler and R.R. Duncan, editors. Turfgrass biology, genetics, and breeding. Wiley, New York.

Ross C. Braun is a lead research scholar, and Aaron J. Patton is interim department head and a professor in the Department of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture at Purdue University, West Lafayette, Ind. Eric Watkins is a professor in the Department of Horticultural Science at the University of Minnesota, St. Paul, Minn. Paul L. Koch is an assistant professor in the Department of Plant Pathology at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wis. Nicole P. Anderson is a field crops Extension agent in the Department of Crop and Soil Science at Oregon State University, Corvallis, Ore. Stacy A. Bonos is a professor in the Department of Plant Biology and Pathology at Rutgers University, New Brunswick, N.J. Leah A. Brilman is the director of product management and technical services at DLF Pickseed USA, Halsey, Ore.